Coquitlam Mayor Richard Stewart isn't buying what a report released last week is selling because its sales appeal is low. Very low.

The report delivered to the Metro Vancouver mayors council on transportation determined what would be needed for the region to reduce traffic congestion in the region and to fund future transportation infrastructure.

"I won't use dead in the water, but I just don't think it has a chance of being approved," said Stewart. "Even if it were something I could support, I think it's chances are very slim, and I have issues with it."

"The independent commission did a really credible job in setting out the issues in finding out whether mobility pricing can be a solution for the region, and now it comes down to putting that report with other discussions we've had about other possibilities. In the end, this is going to require transportation solutions too."

The report prepared by the Mobility Pricing Independent Commission (Coquitlam resident Iain Black, Greater Vancouver Board of Trade CEO and former BC Liberal MLA for Port Moody-Westwood, is a commission member) delves into the details on how two suggested systems could work. One would be to toll specific congestion points. The other would see levies based on how far a vehicle is driven.

Port Moody Mayor Mike Clay said the best thing about the report is it will open up discussion on how to handle a growing region with a perceived inadequate transportation system. But the only way he envisions the public will support it is if the regional gas taxes drivers currently pay at the pump is drawn back.

"This is getting the conversation about the costs and the benefits out in the open and maybe we'll come up with some solutions," said Clay.

The report's analysis models show a regional congestion point charge would cost an "average-paying household" $5 to $8 a day, which works out to $1,800 to $2,700 a year. It would reduce congestion by about 20 to 25 percent and raise $1 billion to $1.5 billion in revenue per year.

Multi-zone, distance-based charges would cost those households $3 to $5, also reduce congestion 20 to 25 per cent and raise between $1 billion to $1.6 billion net annually.

Whatever's decided upon, the commission said the method must deliver meaningful reductions in congestion in a fair way with connections to transit and gives support to investment in transportation infrastructure. The report admits making it a reality won't be easy.

"Changing the way people pay will be politically difficult, and the issues raised by a decongestion charge are many and complex. But the possibilities to support regional goals for quality of life, environment, and the economy are significant," said the report's executive summary.

Stewart said while other jurisdictions around the world have dealt with congestion by other methods, in North American the preferred way is by increasing sprawl and building freeways. "I'm not a believer you can build your way out of congestion."

Coming up with a solution that will work, however, is difficult because regional transportation governance is poorly designed, said Stewart. It's technically a regional function, but not by the regional district (Metro Vancouver), but by a separate company. Metro does plan regional transportation but the execution is carried out by TransLink.

"We've got this weird reality that those functions are done in separate organizations," said Stewart, who chairs Metro Vancouver's regional planning committee.

On top of that, the provincial government makes the big decisions noting the Evergreen Line was initially the next priority after the original Expo line, it wasn't built until after an extension to Surrey, an extension back to Vancouver and the Canada Line to Richmond were completed.

"You wouldn't design a system this way. But the main barrier to doing things is TransLink has no source of funding for this kind of project other than property taxes, and that's only if the region's communities agree to use property taxes for regional transportation. It's a poorly aligned tax, it's regressive and it doesn't connect well with regional transportation," said Stewart.

The report's suggested models for congestion point charges includes all of the region's major bridges and the Massey tunnel. But it also identifies North Road, which is the boundary between Coquitlam and Burnaby as another place to levy a toll.

Since the first he saw of the report was Thursday morning Clay was unaware of why North Road was included. But he wonders if there aren't other congestion points like it that could be considered for tolls, such as St. Johns Street in Port Moody which he said is clogged up in the morning while a parallel route, Como Lake Road in Coquitlam, flows freely in rush hour.

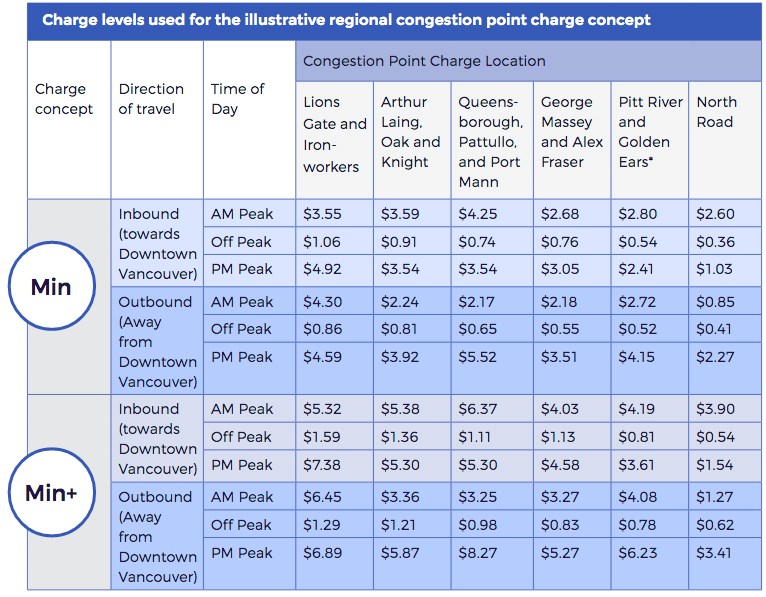

The model suggests varying prices for the different crossings depending on direction and time of day. It also details examples of two rates of scale – minimum and minimum-plus.

For example, rush hour charges range from $8.27 in minimum-plus for traveling south on the Port Mann, Pattullo or Queensborough bridges during the evening drive home to $1.27 for going north on North Road in the mornings. Off peak charges range of 36 cents to $1.29.

The distance-based charge analysis outines up to eight undetermined zones. The biggest drawback to that system, said the report, is the unknown costs of implementing it compared to the congestion point charges, although technology needed for it is developing rapidly which should lower the price tag.

The report said it will take another six to 12 months to develop the concepts into something that could be put into effect. The projected timeline for implementation is two to three years.

The report is the first phase of a feasibility study assessing the affordability and impacts of the options, and what technology is available to make it work.

"Without visionary mobility pricing policy, our population and economy are projected to soon outgrow our transportation network," said the report. "Our region is at a critical juncture. It's time to move us forward.

"Only a small number of people need to change the way they travel for there to be a meaningful reduction in congestion, and most people who change behaviour would not switch to transit. They would change destinations, share cars more, plan their trips more efficiently, and reduce their distances driven. So, while good transit is important in a growing region, the fact that some areas have poorer access to transit is not necessarily a reason to delay the introduction of a decongestion charge."

The report pointed out the NDP government's decision to abandon tolls on the Port Mann and Golden Ears bridges proved the application of charges has to be coordinated.

"The removal of the tolls in September 2017 showed the impacts charges can have on travel behaviour in this region. Traffic volumes across the Pattullo Bridge have been reduced as drivers have chosen the other bridges were are now free, but total traffic volumes have increased."

According to the report, applying token tolls, such as a dollar a crossing, won't work either because while they would generate revenue they wouldn't reduce congestion. "The paradox is that the lower the charge, the more it can be described as a 'tax grab' – only at relatively higher charges do the congestion benefits start to appear."

It noted, cities like London and Stockholm experienced negative reaction and low levels of support when their systems were implemented. Acceptance typically increased after implementation because travel times improved and the negative consequences proved to be less problematic than anticipated.

Clay thinks there are other ways to reduce congestion. He used to work in the warehouse and distribution business and kept its operations open at off hours.

"The truckers loved us," said Clay. "That's the conversation we need to be having.

"Let's start figuring out how to make use of all this infrastructure that sits empty 18 hours a day. How can we better utilize the investments that we are making?"

Clay doesn't think mobility pricing will hurt incumbents in the municipal election campaign this fall because it's likely a decision won't be made until after the Oct. 20 vote. But it will, he said, give strong transit advocates "a chance to stand on that soapbox and say they're behind ideas like this."