When Prime Minister Trudeau suggested recently that travelling and gathering for Thanksgiving might be off book this year, some historians might have experienced déjà vu.

Trudeau warned in a national televised address Sept. 23 that Canada is at a crossroads with COVID-19. Cases in some provinces are climbing, and pandemic conditions are expected to become worse in the coming months than they were when the crisis began in March.

“It’s all too likely we won’t be gathering for Thanksgiving,” he said, “but we still have a shot at Christmas.”

Just over a century ago, when another major pandemic was sweeping the world, a similar message was shared. That year, the government postponed Thanksgiving.

But this wasn’t a big deal. At the time, Thanksgiving Day in Canada was a moveable feast. First observed as an annual national event in post-Confederacy Canada in November 1879, the holiday’s date was determined annually. It had occurred as late as Dec. 6 in some years and even midweek.

It took hard lobbying by the railways to fix it to a Monday. They wanted a holiday long weekend to encourage people to travel — by rail, of course — to visit family. In 1908, the government bowed to the pressure.

But the date of Thanksgiving was still proclaimed annually. Postponing official Thanksgiving Day until Dec. 1 in 1918 was a non-event.

Besides, people had other things on their minds.

They’d already endured four years of restrictions and bad news, thanks to a seemingly interminable First World War. Although the breakthroughs by Allied forces on the distant battlefronts that began in August 1918 brought hope that the fighting might eventually end, the war still ground on, its end undetermined.

Sons, fathers and brothers continued to die in the fighting. In case anyone forgot briefly, telegrams informing families of their loved ones’ deaths arrived frequently in each neighbourhood, and the newspapers published daily lists of those killed or missing in action.

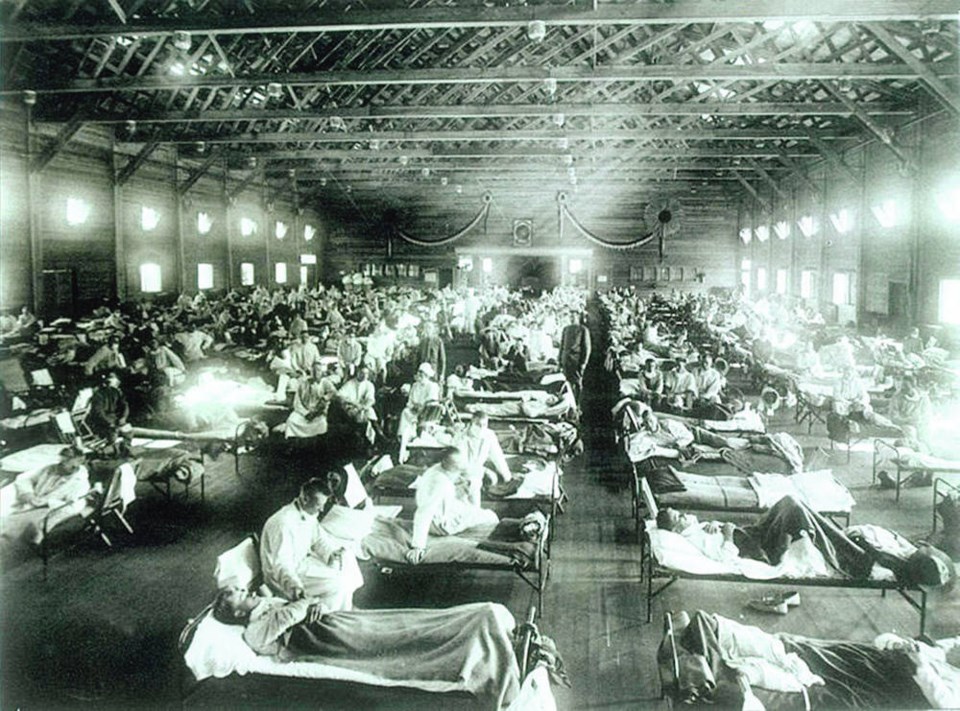

The deadly influenza pandemic was the main reason Thanksgiving 1918 was postponed. Health officials understood limiting public gatherings slowed the flu’s spread. In Victoria, schools, churches, libraries, theatres, colleges and dance halls were closed, and a ban on community gatherings remained in place until Nov. 20.

The Board of Trade cancelled its quarterly meeting, the Canadian Club called off its luncheon with four visiting federal cabinet ministers, the Women’s Auxiliary postponed its annual Thanksgiving drive for donations of linens for the Royal Jubilee Hospital, and meetings and demonstrations to launch the annual Victory Loan campaign were halted.

But by November — then, as now — pandemic fatigue had set in. There were appeals to reopen theatres for “essential” entertainment. Some sporting events started up. Enthusiastic crowds lined downtown streets on Nov. 8 for a Victory Loan parade anticipating the war’s end. And on Nov. 12, the day after the armistice was signed, the Anglican bishop and as many as 1,000 worshippers defied the meeting ban to gather for an outdoor thanksgiving ceremony on Cathedral Hill.

Official Thanksgiving took place three weeks later. At the request of the Dominion Government, Dec. 1 was “observed as a national thanksgiving for the blessings of peace as the result of the great and complete victory of the allied nations over the Central Powers,” according to one Canadian newspaper.

Beginning in 1921, the government combined Thanksgiving and Armistice Day, celebrating both on the Monday of the week of Nov. 11. However, the arrangement, in which solemn remembrance services competed with harvest fairs and sporting events, was deemed insufficiently respectful of veterans. Remembrance Day got its own annual national day in 1931, and Thanksgiving was once again set free to roam Mondays in the fall calendar.

In 1957, Parliament fixed the second Monday in October as Canada’s annual national Thanksgiving Day holiday. We’ve since come to depend on that day for our mid-fall break. We now plan weeks in advance to spend it with family and friends. We book travel and getaways for the long weekend.

This year, however, we’re travelling less and keeping the numbers of those sharing our turkey or turkey-replacement feasts smaller. We may instead be opting for virtual gatherings, as Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s top public health officer, urged last week.

As for our shot at Christmas, let’s wait and see. In 1918, kids in Cowichan Station waited for Christmas until Feb. 15, 1919, when Santa finally recovered from the ’flu.

keiran_monique@rocketmail.com