Most wars begin with a unilateral act. Americans fired “the shot heard round the world” in Lexington in 1775, the Germans invaded Poland in 1939, and the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. To call off a war, however, the belligerents must agree to terms and conditions, a collaborative and convoluted process.

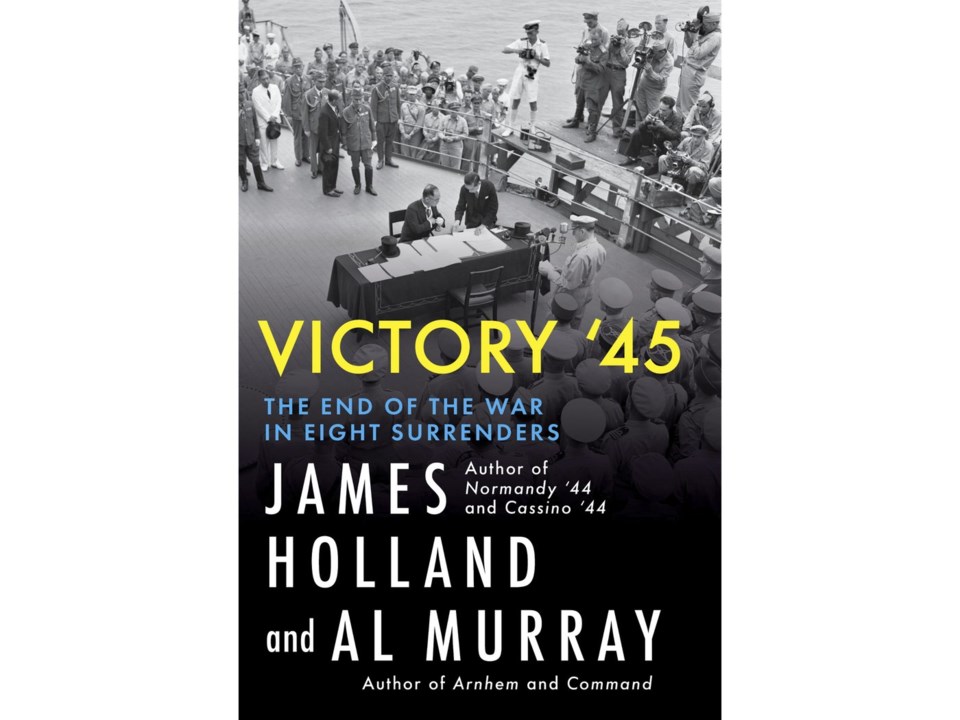

In the popular imagination, World War II concluded in 1945 with the deaths of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in Europe, and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. As historians James Holland and Al Murray chronicle in their finely detailed book “Victory ’45: The End of the War in Eight Surrenders,” those events alone were not capable of halting the colossal military might unleashed over the previous six years.

Consider how the ultimate aim of the Allies — unconditional surrender as set in a joint declaration — contrasted with the Nazi blood oath calling for a “1,000-year Reich or Armageddon.” President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, meeting in Casablanca in January 1943, outlined the strategic, political, and moral clarity necessary to fight a global conflict. By spring 1945 Hitler and his supporters were rotting in his Berlin bunker.

Holland and Murray use the bunker setting — depicted in the 2004 German film “Downfall“ featuring a meme-able Hitler tirade — as the predicate for the multiple European surrenders to come. If rehashing Hitler’s suicide, in April 1945, early in the book seems anti-climactic, “Victory ’45” justifies itself by moving on to the unsung but equally dramatic tales of those who navigated the confusion of a war that was won but hardly finished.

The first significant capitulation began weeks earlier when two backstabbing rivals in the Nazi SS high command in Northern Italy separately schemed to save their own postwar skins. Their intrigues delayed the first of Europe’s unconditional surrenders, limited to their sector, signed just a day before Hitler’s demise. A recurring motif was the futile attempts by the Germans to only yield to the West in hopes of splintering the Allies and escaping Soviet vengeance.

While Holland and Murray include brief profiles of famous politicians and commanders as further European surrender ceremonies were staged and announced, “Victory ’45” finds its relevance and poignancy when it directs its focus downward. There, ordinary individuals journeyed to the intersections of triumph and despair, relief and revulsion.

Examples include the Jewish-American college student haunted by the atrocities at a slave compound in Austria seized by his Army unit. Those rescued included a Jewish-Czech teen who lied about his age to avoid extermination at Auschwitz and joined his father in surviving stints at multiple camps. Liberation was punctuated by grief just days later in a makeshift hospital when his father died in his arms.

On the Eastern Front, a young female translator in Soviet military intelligence was integral to a search in Germany’s devastated capital. Were the reports of the Fuhrer’s death Nazi disinformation? She interrogated captured witnesses, attended the autopsy of the burned corpse, and was even given custody of the teeth that were eventually confirmed as Hitler’s. Not much further west, a bedraggled teenage German conscript who did escape Berlin’s aftermath lived on the run until captured by a Russian soldier who simply told him, “War is over! All go home!”

Turning to the Pacific Theater, “Victory ‘45” examines the grim prospect the Western Allies faced in “unconditionally” conquering a warrior ethos in Japan, epitomized by their civilians’ suicidal resistance to the Allied invasion of Okinawa. The necessity of the atomic bombings was proven by the attempted military coup staged by high-ranking Japanese holdouts who wanted to defy Emperor Hirohito’s orders and continue fighting despite the threat of nuclear annihilation.

Not simply targeted to WWII enthusiasts, “Victory ’45” illustrates for those with a broader historical interest the myriad challenges in bringing to heel the dogs of war. Brits Holland and Murray cannot be expected to quote Yankee baseball legend Yogi Berra, but their book deftly explains 80 years later why in war as well as sports, “It ain’t over ’til it’s over.”

___

Douglass K. Daniel is the author of “Kill — Do Not Release: Censored Marine Corps Stories from World War II” (Fordham University Press).

___

AP book reviews: https://apnews.com/hub/book-reviews

Douglass K. Daniel, The Associated Press