If you think the current internment of Mexican and Central American migrants at the U.S. border is shameful, consider B.C.’s actions against its “enemy alien” residents of Japanese-Canadian heritage nearly 80 years ago.

Shortly after the American navy was attacked at Pearl Harbor in 1941, Canadian prime minister Mackenzie King banned Japanese nationals and Japanese-Canadians from the Pacific coast in the interests of national security as they were feared to be potential spies.

A poster from the BC Security Commission circulated with the names of the places from which they were prohibited — among them, Burquitlam, Port Moody, Ioco, Port Coquitlam, Maillardville and Fraser Mills, the area in south Coquitlam once home to the Commonwealth’s largest sawmill.

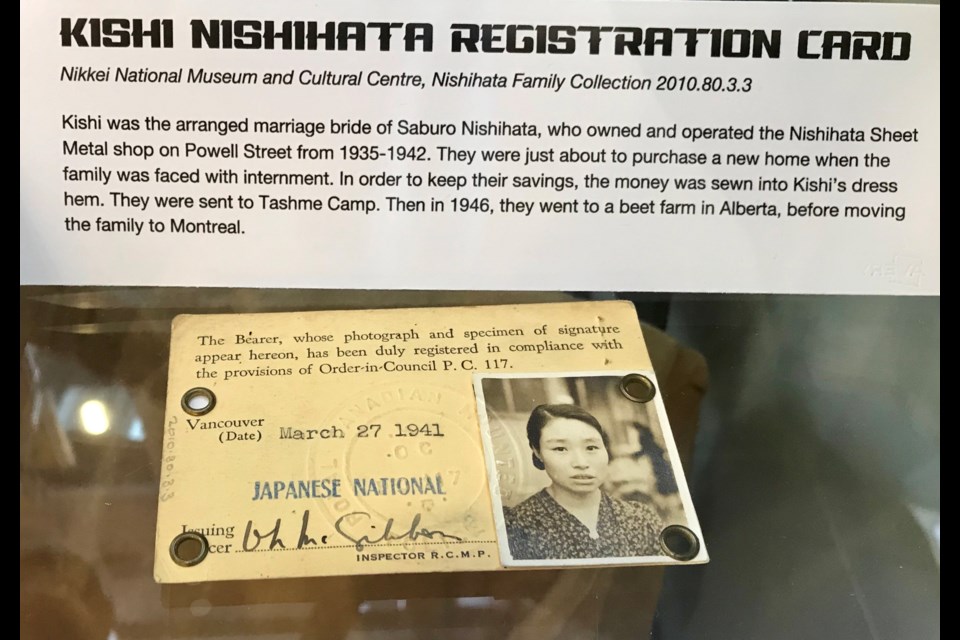

A copy of that poster and dozens of other artefacts and photos borrowed from the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre as well as the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, in Ontario, are now on show at the City Centre branch of Coquitlam Public Library (1169 Pinetree Way).

Titled Resilience: The Internment of Japanese Canadians, the small exhibit was curated by Tannis Koskela, heritage manager for the Coquitlam Heritage Society, as a “teaser” for the society’s next major display at Mackin House: The Home Front, a Second World War show that runs from September 2019 to June 2020.

Located in the library lobby, Koskela’s exhibit is split into three periods: the Japanese-Canadians’ influence in and around Vancouver before WWII; the camps that saw some 22,000 people of Japanese origin interned; and the redress by prime minister Brian Mulroney in 1988, which included an apology and a compensation package.

Koskela also tried to tie in as many Tri-City connections as she could find, as many Japanese-Canadians worked in the lumber and fishing industries. “There was a large Japanese community in Fraser Mills and Sapperton [in New Westminster],” said Candrina Bailey, the society’s executive director.

Prior to Canada declaring war on Japan, Japanese-Canadians centred many activities and companies in Japantown, around the Powell Street area of Vancouver. Koskela included a large framed 1938 calendar from Yama Taxi, the largest taxi service in Japantown and started in 1915 by Shintaro Yamashita. His assets were seized when he was sent to the Minto Mine camp.

Koskela also included an image of the Asahi Baseball Club that was established in 1914 in Japantown and disbanded when its players were shipped to internment camps (its legacy was honoured this year with a Heritage Minute commercial and a Canada Post stamp). The display has a bat used by the team and a new baseball signed by the last surviving member of the team: Koichi Kaye Kaminishi.

For the camp section of the exhibit, Koskela shares the stories of two Tri-City residents: Sgt. Masumi Mitsui of the 10th Battalion served in France in the First World War but, in 1942, was hauled off his chicken farm in Port Coquitlam to be interned at the Greenwood camp. Kunizo Konishi, a Flavelle millworker who owned a home on Maude Road and a Burquitlam farm, was sent to the Angler prisoner-of-war camp in Ontario.

Many labourers in the B.C. war camps built highways 1, 3, 6, 12 and 31. The children read books, carved wood and played baseball; some of their artefacts are on display. The prisoners weren’t allowed to return home until 1949 — four years after the war ended.

The redress section of the exhibit includes a T-shirt and apron with the logo “Canadians for Redress.”

Michael Abe, project manager of Landscapes of Injustice, will speak at Mackin House in Coquitlam Nov. 9 from 1 to 3 p.m. about the mass displacement and dispossession of Japanese-Canadians. To register for the talk, visit coquitlamheritage.ca.