Logging companies cut at least 4,000 hectares of some of B.C.’s biggest old-growth forests since the province promised to halt operations, new satellite data shows.

About 2,600 hectares of that forest — almost all big ancient trees — were slated for deferral by the province, but was logged anyways, according to the numbers. The old-growth loss is equivalent to an area nearly 6.5 times that of the Stanley Park, but only represents a fraction of what has actually been taken, said Tegan Hansen, a senior forest campaigner with Stand.earth.

“Often, we'll hear government or industry talk about there being no shortage of old growth. But the reality is we're mostly seeing priority big-treed growth deferrals getting targeted, which is the most rare kinds of old growth we have left in B.C.,” Hansen said.

The environmental group gathered the data through a new satellite watchdog platform, launched Thursday under the banner Forest Eye. The technology, built with the help of the satellite firm Planet Labs, systematically tracks forest cover change across the province since the B.C. government promised to halt logging in big treed old-growth forests nearly three years ago.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Forests said the province has deferred 2.25 million hectares of old-growth forests since November 2021. But by December 2022, the ministry spokesperson said another 11,578 hectares of old growth that was flagged for protection has since been logged — 4.5 times the initial satellite estimates. The spokesperson said those harvests occurred where the province and First Nations couldn't find a consensus to defer logging operations.

Old-growth deferrals are meant to halt logging and remain in place until long-term plans to overhaul forestry practices can take effect. The province says it seeks to reorient the industry to prioritize the health of forest ecosystems and long-term resilience of communities in line with recommendations from a 2020 Old Growth Strategic Review.

But Stand.earth says the B.C. government's promises have not been backed up with transparent reporting on the ground, especially when that involves failure to protect old trees. The group's open-source map uses the province's own data identifying areas slated for priority deferral. It doesn’t include recreational permits, tree farm licences, community forests or any forest loss due to wildfires. Permits before 2020 and after 2030 are also excluded.

Members of the public can sign up to receive email or text message alerts when new old-growth logging is flagged. The map allows anyone to track the logging company involved, how much has been cut and whether taxpayers were enriched by the activity. Alerts also include high-resolution satellite imagery and time-lapse videos showing how forest cutbacks have changed.

While only presenting a partial picture of old-growth logging in B.C., the maps reveal how sanctioned logging practices — from road building to harvesting — are occurring in areas flagged for conservation.

“You can see the progression of logging,” said Hansen. “We want people to know what's going on.”

Old-growth clear-cut collides with wildfire

About 225 kilometres north of Mackenzie, B.C., the Akie and Finlay rivers merge between the peaks of two provincial parks.

More than half of a nearby 281-hectare forest lot was destined to be deferred because of its priority big treed old-growth status. But in March 2022, the province auctioned it off to Trent Gainer, and in January 2023, the land was cleared of trees, according to satellite data shared on the Forest Eye platform.

Four months later, a time-lapse video shows a wildfire tearing through area, burning around and through the cut block. The wildfire has so far burned more than 17,000 hectares of land, a relatively small but significant contribution to what has become the most destructive wildfire season in B.C.’s recorded history.

"We know that these styles of logging make these landscapes a lot more susceptible to massive fires," said Hansen.

Angeline Robertson, a senior investigative researcher with Stand.earth, said that’s because even smaller northern forests absorb water like sponges, making them especially important during periods of extreme drought and burning.

“They store a lot of water,” she said. “When it comes to these old forests and the kind of climate crisis we're in these days, the math [behind cutting these trees] doesn't add up anymore. Maybe it never did.”

1,300 hectares of candidate deferral old growth logged on Eby’s watch

Robertson and her colleagues have only begun to filter through the past three years of satellite data feeding the Forest Eye technology.

So far, they have screened 300 alerts, representing more than 4,000 hectares of logged old-growth forest since 2020. About 2,600 hectares of that forest was slated for deferral by the province, but was logged anyways — including 1,300 hectares since Premier David Eby took office.

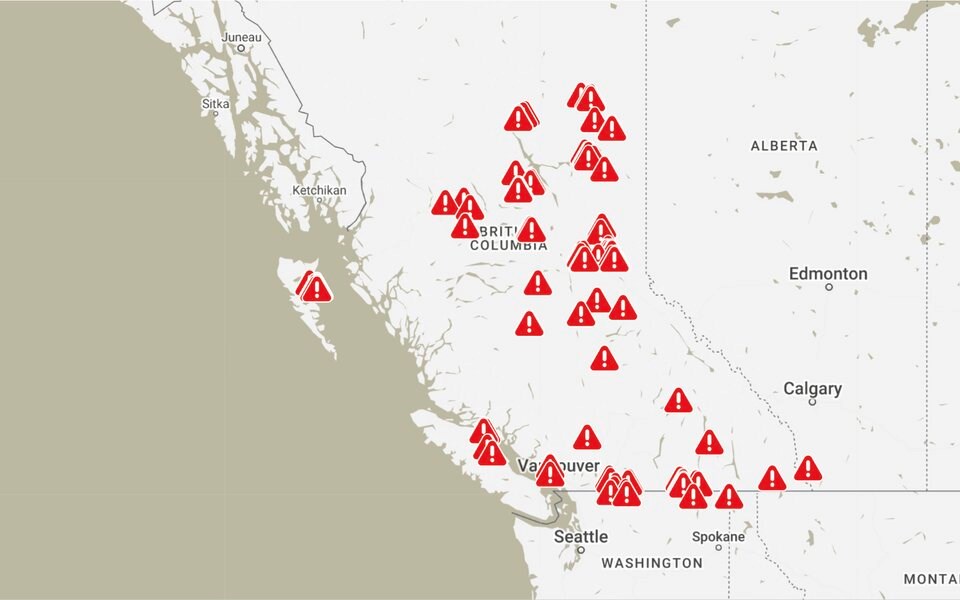

Some of the locations screened and posted to the map so far include:

- three cut blocks on the Sunshine Coast;

- one outside of Pemberton;

- several in the Fraser Valley north of Chilliwack and Hope;

- dozens spread out across the Southern Interior;

- and several more on Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii.

The largest concentrations of old-growth cut blocks currently appearing on the Forest Eye map are in B.C.'s central and northeast regions, surrounding communities like Prince George, Smithers, and a large swath of land northwest of Fort St. John.

But Robertson said none of that is representative of the growing tally, as her team is still trying to work its way through another 400 alerts, screening them to make sure the data is accurate before uploading them to the map. Another 10 to 20 alerts are coming in every day.

In a few months, Robertson said her team plans to review the data to provide snapshots of how logging is impacting B.C.’s biggest trees. Hansen said the group hopes to identify trends in the same way satellite mapping projects monitor illegal logging in the world’s tropical forests — and in their own way — fill the logging transparency gap left by the B.C. government.

“All this information comes from the government. All of the tools and software that we've employed they have access to,” said Robertson.

“So the question remains, why are we having to fill this gap?”

Mapping project comes amid battle over future of Canada’s forests

In March, Stand.earth together with the Wilderness Committee and Sierra Club BC released a report finding 55 per cent of B.C.’s most threatened old-growth forests are still open to logging. The report card gave the B.C. government an 'F' for its lack of transparency and communication, stating it has "repeatedly cherry-picked data to exaggerate limited progress to date."

The debate over the future of forestry is also heating up at the federal level. Canadian forestry regulations require companies to replant trees after they have been logged. The “sustained yield” model, as it’s known, has long framed Canadian forestry as an endlessly renewable resource. But that logic has been increasingly questioned in recent years as many species that rely on the forest are pushed closer to extinction.

Canada moved to come up with its own domestic definition of forest degradation shortly after the European Union passed a law that would restrict forest products linked to deforestation and forest degradation. Some critics worry it's an attempt to find a trade loophole and continue business as usual; others say it could offer a path to reset how Canada manages its forests in an era of climate change.

The government data Forest Eye is collecting worries Hansen that not much has changed. When an old-growth stand is clear-cut, it takes hundreds of years to return. Hansen said that in many cases, forests aren’t being given that chance to come back, instead being turned into mono-crop plantations and sprayed with glyphosate to eliminate fire-resistant species.

“Effectively, we are destroying these forests,” said Hansen. “It's not considered illegal logging because it is permitted by our governments.”

Climate change is compounding the problem. On B.C.’s coast, species like cedar are struggling to grow back. In the Interior, a 2020 investigation from the Forest Practices Board found an over-reliance on clear-cutting contributed to a situation where 60 per cent of the cut blocks examined were in “poor and marginal conditions” at a time climate change is making wildfires worse.

“Long-term timber production in some dry-belt fir ecosystems may not be feasible or realistic in the future,” noted the special investigation.

A map built to empower the public

The scale of logging in B.C., let alone Canada, can be hard to fathom. So while Forest Eye automatically flags old-growth logging across the whole province, it is designed to help people understand what’s happening in forests either next door or down a remote logging road thousands of kilometres away.

Hansen said her group will support people who want to present the information to elected officials, or use it in their communities to ask questions.

“This tool kind of removes a huge barrier,” she said. “It puts that information in the hands of the public. It’s going to be incredibly empowering.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated with comments from the B.C. Ministry of Forests.