Warning: This story has details about acts of violence against children.

Three years after her 19-month-old daughter was apprehended by the Nuu-chah-nulth child protection agency and placed in a home where she was beaten to death, Julie Frank said she wanted to make sure future children in care would be protected.

Frank, the mother of Sherry Charlie — whose death ended up being the focus of intense political scrutiny in B.C. — said the provincial government and USMA, the child-protection agency, needed to follow proper procedures so children in care would never be placed in homes where they are unsafe.

“I just want to make sure that they never do this to anyone again,” Frank, who was 19 when she had Sherry, told the Times Colonist in September 2005.

Not only has it happened again — it happened to a member of Frank’s extended family.

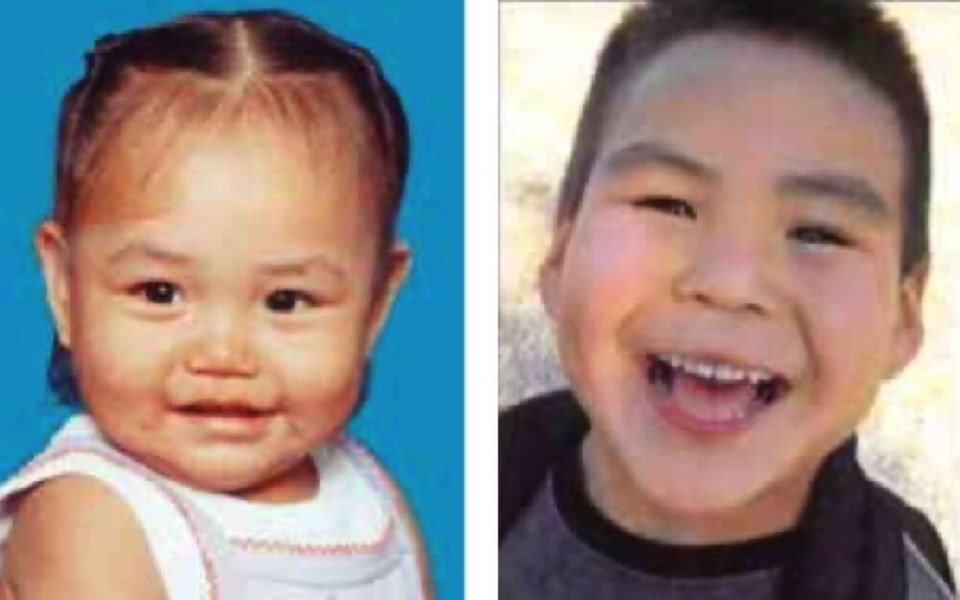

Dontay Patrick Lucas died on March 13, 2018, of blunt force trauma to the brain after being transitioned back into the care of his mother by USMA Nuu-chah-nulth family and child services.

Dontay and Sherry were members of the same family. The Lucas family and the Frank family are related, Dontay’s father, Patrick Lucas, confirmed this week. Julie Frank is his auntie, said Lucas. Dontay and Sherry were cousins.

Dontay’s mother, Rykel Charleson, and stepfather, Mitchell Frank, were accused of depriving the little boy of water, food and sleep, hitting and biting him. The couple, who were originally charged with first-degree murder, pleaded guilty to manslaughter and are to be sentenced in Port Alberni on May 16 and 17.

In September 2002, 19-month-old Sherry Charlie was beaten to death less than a month after she and her older brother Jamie were placed in the home of her aunt Claudette Lucas by USMA.

Sherry was killed by the aunt’s common-law partner Ryan Dexter George, who was on probation for spousal assault and had a previous record for robbery with violence and arson.

He confessed that when Sherry wouldn’t stop crying, he banged her head on the floor several times and stepped on her stomach.

George pleaded guilty to manslaughter in 2004 and was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Sherry’s death came under scrutiny after the then-B.C. Liberal government released a long-awaited review of the case that cited poor communication and lax procedures between child welfare agencies.

The review concluded Sherry was placed in the home even though the Ministry of Children and Family Development and USMA had yet to complete all the proper criminal and family checks on the George home.

It sparked at least six other reviews of the handling of Sherry’s case, including an independent probe of child protection in the province by Ted Hughes, a former judge and B.C. conflict-of-interest commissioner.

More than 70 individuals with special expertise and over 300 child welfare groups contribute to the review.

Five months later, Hughes submitted the B.C. Children and Youth Review to the provincial government, with 62 recommendations for changes to the child welfare system, including the creation of an independent advocacy and oversight body — the Representative for Children and Youth.

In Dontay’s case, Representative Jennifer Charlesworth released a statement saying she made the decision not to conduct a full investigation into the child’s life and death due to a number of factors, including the potential further harm and trauma it could cause the family and community, and the amount of time that had passed since his death and how that might affect the quality of the investigation.

Asked again during an interview if she was considering a full investigation, Charlesworth said she is “always kind of reviewing.”

“My question is: Can I do something meaningful for this little boy and what’s happened to him to prevent further harms being caused to children in situations like this in another way?”

Dontay’s story will likely be woven into the office’s review of child well-being and supports in B.C. that will be released in June, she said.

Many questions remain unanswered. It’s not known why Dontay was returned to his mother after being in foster care for five years. It’s not known if any USMA staff responsible for Dontay’s care were related to his family.

It’s also not known why multiple reports of neglect and abuse of Dontay in his mother’s home were not addressed before his death.

Patrick Lucas is pushing for a full investigation into his son’s death, said family spokesman Graham Hughes.

“What we are looking for is to understand why Patrick’s family was left out of any information about Dontay returning home. We are looking for an investigation to see how many days he was absent from school and why they were not doing in-person checks in the home,” said Hughes.

“And who got to make that call that it would be too upsetting for the community to know about Dontay’s death? Because we’re going back to Sherry Charlie’s case where they weren’t doing due diligence in the environment they were putting a child into and the child died.”

Christmas was very difficult this year, said Lucas, who said he last saw his son on Dec. 17, 2017.

“[Christmas] was always one of his favourite times of year,” he said, adding Dontay’s birthday was Dec. 31.

To mark the occasion, immediate family gathered for cake and prayers, Lucas said.

“He would have been 12 years old.”

The B.C. Coroners Service has yet to complete its investigation into Dontay’s death.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]