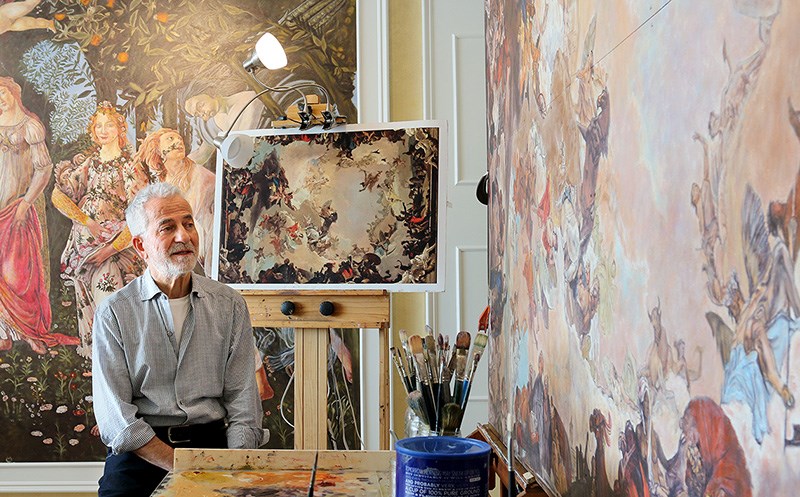

Cosimo Geracitano is a slight man with closely cropped grey hair, a neatly trimmed beard and watery, green eyes that betray a constant wonder of the beauty that surrounds him.

His hands hold the precision of draftsman and the ingenuity of an engineer. The Coquitlam man is an inveterate tinkerer, collector and dreamer, inspired as much by the windswept lines of a Rosso Corsa-red Ferrari as he is by the liberté, égalité and fraternité of Lady Liberty.

And, at 71, Geracitano has painted himself into a corner.

'I painted a ship'

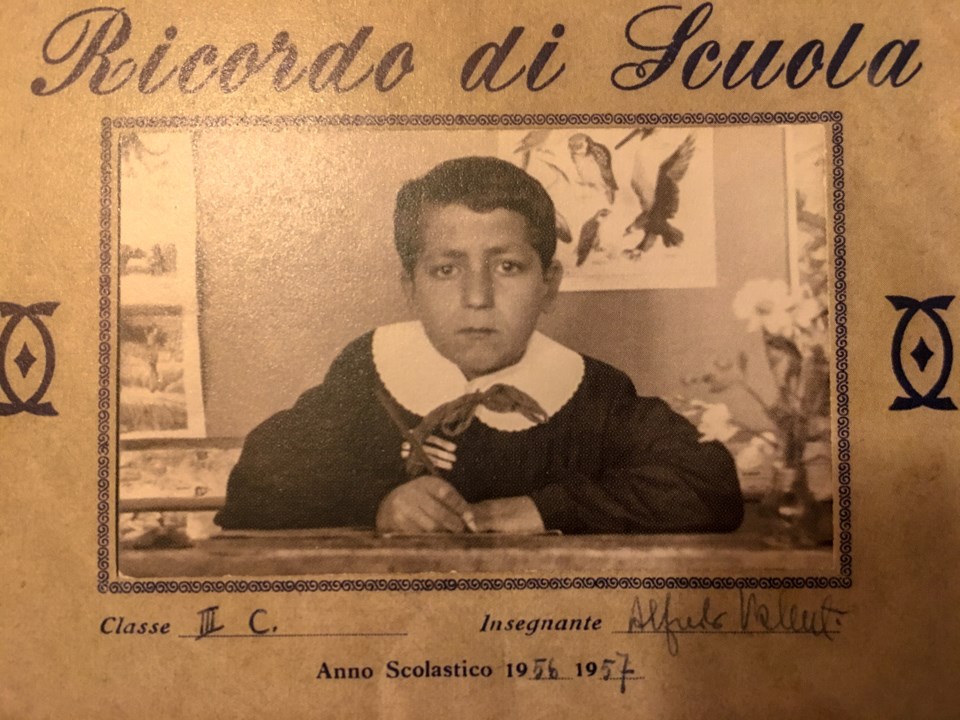

Geracitano was born in the thousand-year-old, thousand-person town of Bivongi, Reggio Calabria, on the sole of Italy’s boot. From a young age, he had the keen sense of history of someone who grew up in a single-room house built on 700 years of continuous settlement, where “rooms piled up on top of each other.”

Still, he told The Tri-City News, “I dreamed always of leaving.”

The other thing that occupied his thoughts was painting.

His earliest memory of painting was on the stone wall of his house, high off the ground. “I leaned like this out a tiny balcony,” he says, arching over and miming paintbrush strokes. “I painted a ship.”

By the time he was 19, Geracitano had finished school as a naval mechanic and began shuttling across the country in search of jobs. When he struggled to find work, his father mentioned there was a man in town offering papers to people with diplomas who wanted to move to Canada.

“So I went to see this guy,” he says. “Finally, I got my dream to go on a vessel.”

Geracitano landed at Halifax’s Pier 21 in 1967, soon settling in Toronto, though unable to speak a word of English.

He got a job, fell in love, got married and had three children. By the time his oldest was seven, he had stopped painting. He started his one company, doing electric motor and generator repairs, then another: a car dealership selling exotic Lotuses, Alfa Romeos and Lamborghinis.

"I got busy. I didn't paint for 25 years.”

By the late 1980s, the family got “tired of the snow,” picked up and moved west, settling in the Tri-Cities.

Over the years, the thought of painting haunted him, until a decade ago, just after he retired, he pulled out his 25-year-old easel and paints, cracking open the seized tubes with pliers.

“Inside, the paint was still good, so I started painting.”

Special hands

His return to painting started with a few originals, family portraits, a scene from a trip to Italy.

But those early creations never seemed enough.

Late in his career, as his son took over his electric motor repair shop, Geracitano had carried over his obsessive work ethic into his art, carving a 151-lb. book, The Stone of Hope, out of solid jade, a stone harder than steel.

As his daughter wrote in a history of the sculpture: “The project consumed him and interfered with his every activity: eating, sleeping, driving.” He wrote down ideas at stoplights, Post-It notes littering the steering wheel and dashboard.

The tools to carve such a jade book did not exist, so Geracitano built his own diamond-tipped saws, some blades as tall as a man. With precision, he cut, drilled, sanded and carved for thousands of hours until, from a single block, the likenesses of and quotations from Mahatma Ghandi, Martin Luther King Jr. and Mother Teresa rose from the pages in shallow relief, each page freed from the block along the arched jade bindings.

“When I was a little kid, my mother told me that I have special hands, [that] I could be a surgeon or a professor,” he told The Tri-City News. “Now I know why. I can do those things that most people can't.”

A home, a museum

Perched on a sleepy side street on Westwood Plateau, Geracitano’s house is a tall, modern structure, unremarkable from the outside. But walk through the front door and you immediately find yourself in rooms with the hushed lighting of a museum. The living room reveals dozens of duplicates of masterpieces, a "best-of" stretching from the 1400s to the turn of the 20th century.

In Raphael’s renaissance-era gift for Pope Leo X, St. Michael rises up towards the vaulted ceiling, vanquishing Satan with his spear. You catch fleeting glimpses of the Mona Lisa and The Girl with the Pearl Earring before your eyes are inevitably drawn upward, your neck cranking back so you can take in The Creation of Adam, Michelangelo’s inverted fresco from the Sistine Chapel.

“You see this one here?” says Geracitano, waving to his version of Claude Lorrain’s 1641 Baroque interpretation of the Saint Ursula legend. “This one is 600 hours of work.”

Over the last decade, Geracitano has produced 45 replicas of some of the most famous paintings in the world and, in the process, has turned his home into a private homage to some of the greatest artists Europe has ever known.

He has taken to leaving the lights on, each painting illuminated with special low-voltage tape. “Four o'clock [in the morning], I’m up,” he says. “I get inspired, take the brush and I can do anything.”

Like The Stone of Hope before, the process of replicating masterworks of art is both labour-intensive and exacting. Every year, Geracitano travels to western art’s most famous museums: the Louvre in Paris, the Met in New York and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. He’ll sit for hours, examining every last detail before picking up the most expensive, detailed posters he can find.

“Every little line, everything I do, I go with a magnifying glass and pick up every touch of paint or pencil. Line by line. It's not simple,” he says.

For some paintings, he has gone to museum websites, pulling up high-quality digital photographs and zooming in. For others, he’ll divide the digital copy into grids, printing off a series of 8½- 11-inch pages to assemble a forensic template.

“I zoom in and what appears to be just a line, it's people,” he added pointing to the rigging on one of Lorrain’s ships. “It's people climbing the ladder there. There’re people everywhere, over a 110 people in here. You don't see them.”

By mixing his own colours, Geracitano strives to capture what the originals looked like when they were finished — recreating but restoring at the same time.

He studies the direction of each brush stroke and the texture it leaves on the canvas. While the original artists produced their works in moments of inspiration, Geracitano says it will take him months to replicate their genius.

“When I like something — the more difficult, the better — I'll find a way,” he says.

No more space

Now, he has to find some space, whether in his home — where he also keeps a 1987 Testarossa, which he calls "the poor man's Ferrari" and which is housed in a garage adorned with an eight-foot tall, 16-foot-wide replica of Rosa Bonheur’s 1850 masterpiece, The Horse Fair — or his life.

On a whim, Geracitano will move furniture from room to room transforming the dining room, kitchen or living room into a temporary studio. He often paints under his own replica portraits of Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo, trying to channel their presence.

“This is a way you can get close. For me, it's getting this feeling, the vibration from the painting about the artist and the subject,” he says.

Painting has also been a way for him to get closer to the culture he left behind in Italy, something he says he can talk about for hours.

And over the last few years, Geracitano’s all-consuming approach to art has deepened. Since his wife passed away nearly four years ago, he has produced 20 paintings.

Now, he has reached a tipping point: There is no room left on his walls.

His 46th replica — the last, he says — takes up nearly all the space in the dining room. Over the Easter long weekend, Geracitano installed the exquisitely detailed replica of Giovanni Battista’s 1752 painting Allegory of the Planets and Continents on the ceiling of his dining room.

“I've been slowing down lately," he says. "This is my last painting. It's a big one, one of the most complicated."

Slowing down?

But maybe it's not his last.

Earlier this year, he decided to play a prank with his girlfriend, Mona, an interior designer and art collector.

In 2017, Salvator Mundi — a painting of Jesus Christ attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci — fetched U.S. $450.3 million at auction. After the world’s most expensive painting mysteriously went missing last fall, Mona sent the National Post a photograph of Geracitano standing in front of his replica with a note reading, “Do you really want to know where the Salvator Mundi is?”

A flurry of press coverage followed: The BBC, Inside Edition and the CBC all descended on Geracitano’s home to report on the former repair man and his vast collection of duplicates.

Since then, Geracitano has received about a dozen requests for replicas from as far away as Scotland, Brazil and Australia. While the attention has been somewhat overwhelming, the timing may not work for Geracitano, who says he does a couple of commissions each year but he’s ready for a change.

So while in one breath he says he's slowing down, in another, he says, "You know, we want to have fun. We're still young. We want to travel. We don't want to paint everyday.

"I’m only 71, I’m in the prime of my life.”

---

Can you tell which version of Rudolf Koller's Gotthard Post is the original, and which is Geracitano replica?

Stefan Labbé