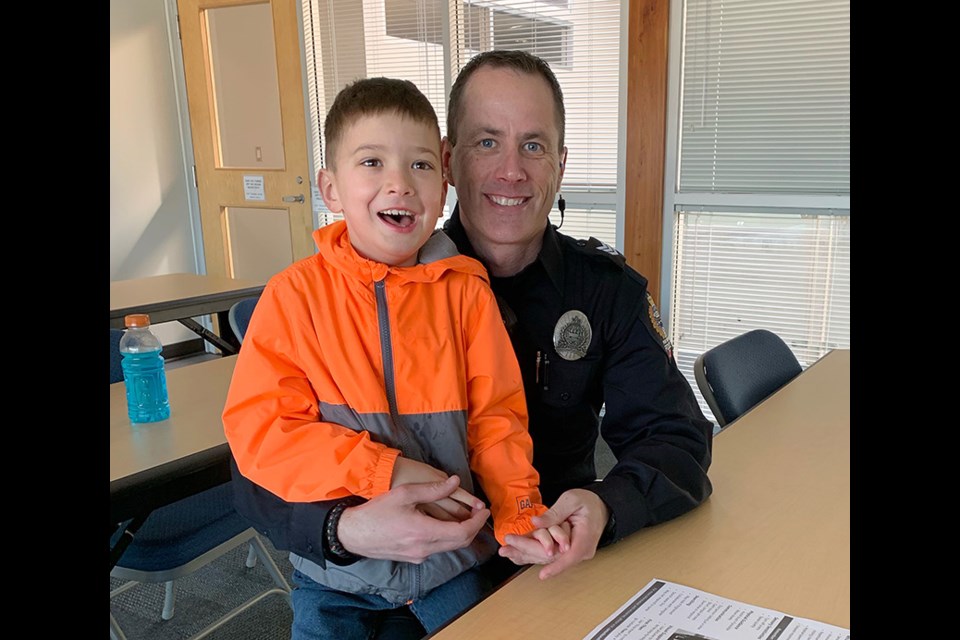

Rob DeGoey hopes his seven-year-old son, Kayen, never has an encounter with police. But if he does, his dad wants to ensure officers have the tools and training so they don’t mistake behaviours brought on by his autism as non-compliant or threatening.

A new online training module developed by the Canucks Autism Network (CAN) will give Port Moody police those tools.

DeGoey said the diagnosis of his son's developmental disorder four years ago sent his family “into a tailspin.” But as a youth liaison officer with the Port Moody police department, he also knew his son’s tendency to wander and his repetitive behaviours when in a stressful situation could “present as a risk” to people who don’t know him, especially first responders like police.

As part of his own education about autism, DeGoey toured the Pacific Autism Family Network in Richmond, which provides supports for people and families affected by autism.

“It really opened my eyes,” DeGoey said. “It planted the seed in my mind to do something in Port Moody.”

That seed grew to his involvement with CAN to help develop the new program, which also includes in-person training for a variety of possible scenarios.

Port Moody Police Chief Const. Dave Fleugel said the additional training for the department’s 55 officers and more than a dozen civilian employees was a slam-dunk.

“If we have the education, then we can adjust,” Fleugel said, adding officers have to deal appropriately with every situation, especially when it comes to people with special needs or circumstances.

Hallie Mitchell, the director of training at CAN, said since the online program was launched in January, more than 650 people — a range of first responders, including police, firefighters, RCMP, BC Emergency Health Services and government workers — have registered. She said the online model allows the training to reach more people, including first responders from other provinces who’ve shown interest in the program.

Hallie said with one in 46 children in B.C. diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum, and one in seven of individuals on the spectrum likely to have an encounter with first responders, providing those emergency personnel with the understanding to identify behaviours associated with autism and the tools for responding is critical.

“Without training, they can respond in a way that inadvertently makes a situation worse,” she said, adding the representatives from various first responder groups who played a role in creating the program were able to draw upon some of their own experiences.

DeGoey said parents aren’t always forthcoming about an autism diagnosis right away and a simple misunderstanding or misinterpretation can quickly escalate.

“That’s the fear of every parent,” he said.

Fleugel said as police departments increasingly deal with calls that are more of a social service nature than criminal, they have to broaden their skills.

“It’s one piece of the pie,” he said. “Not every call needs handcuffs.”

• DeGoey is a finalist for an Autism BC excellence in autism award as its volunteer of the year that will be presented April 26.

What does autism look like?

Here’s what autism can look like, according to a tip sheet for police produced by the Canucks Autism Network:

• sensory sensitivity, like covering ears;

• unusual eye contact;

• repetitive motor movements like rocking or hand flapping;

• atypical speech or lack of speech;

• delayed responses;

• challenges with social interactions;

• may not feel cold or pain in a typical way;

• impaired sense of danger that may lead to wander into water or traffic;

• may not recognize first responders as helpers.

4/10: Clarified statistics of individuals with autism