An international collaboration to breathe new life into more than a dozen B.C. cold cases — including two in the Tri-Cities — has led to the release of 14 skull reconstructions recreated through 3D printing and the artistic talent of students at a New York art school.

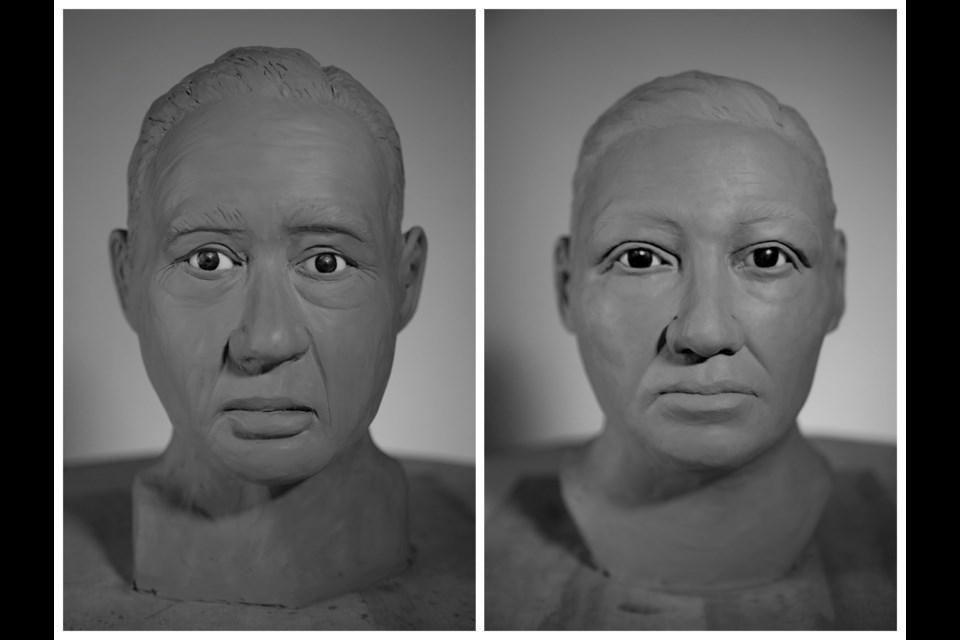

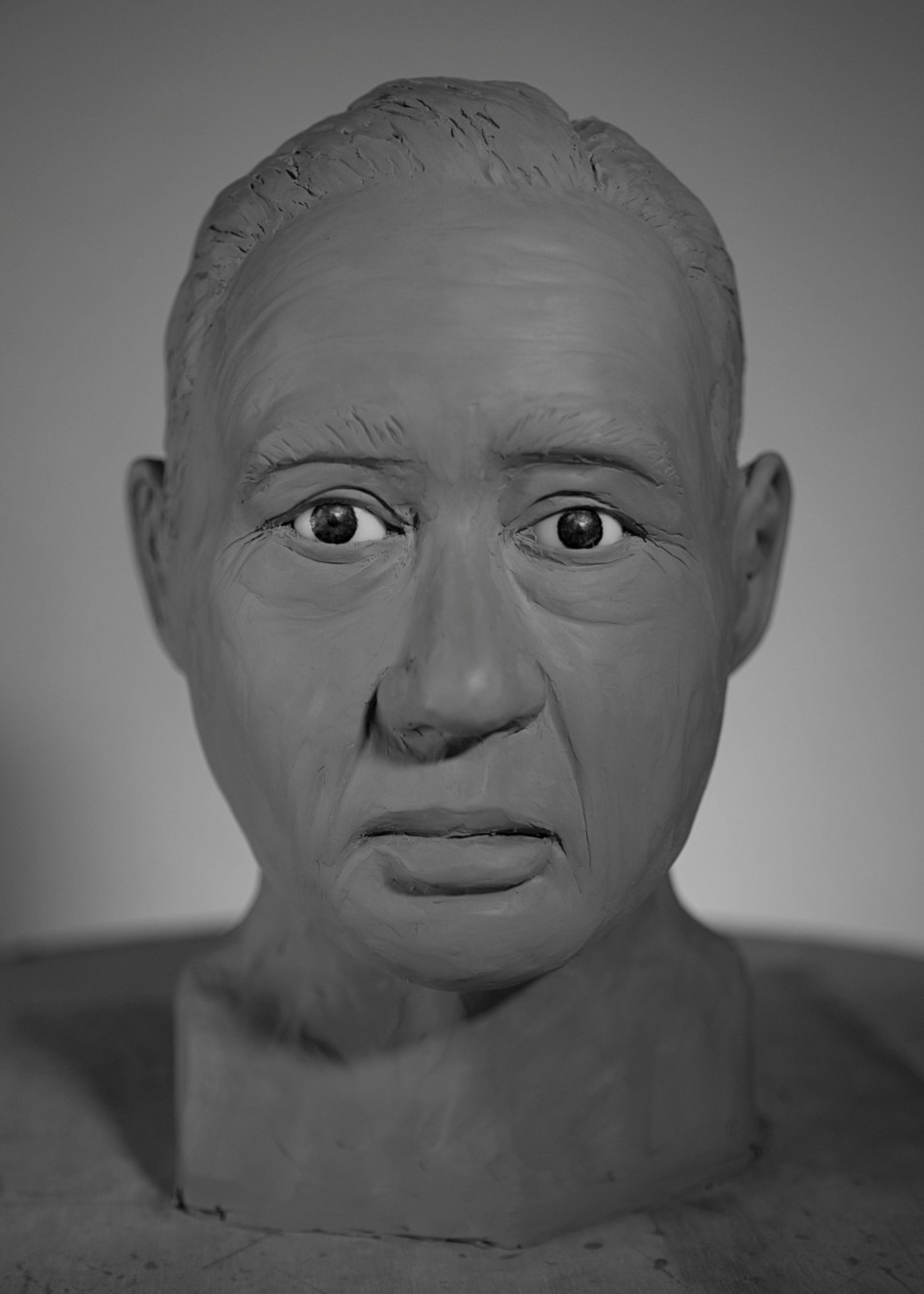

The cases date back to 1972 and include the unidentified remains of a man found dead in 1995 in the waters near Port Moody’s Reed Point Marina. A BC Coroners Service document described the man as between five feet four inches and five feet six inches tall, wearing a Rapier brand long-sleeved khaki shirt, a white T-shirt, blue dress pants and an Edmonton Psych Centre underwear when he was found.

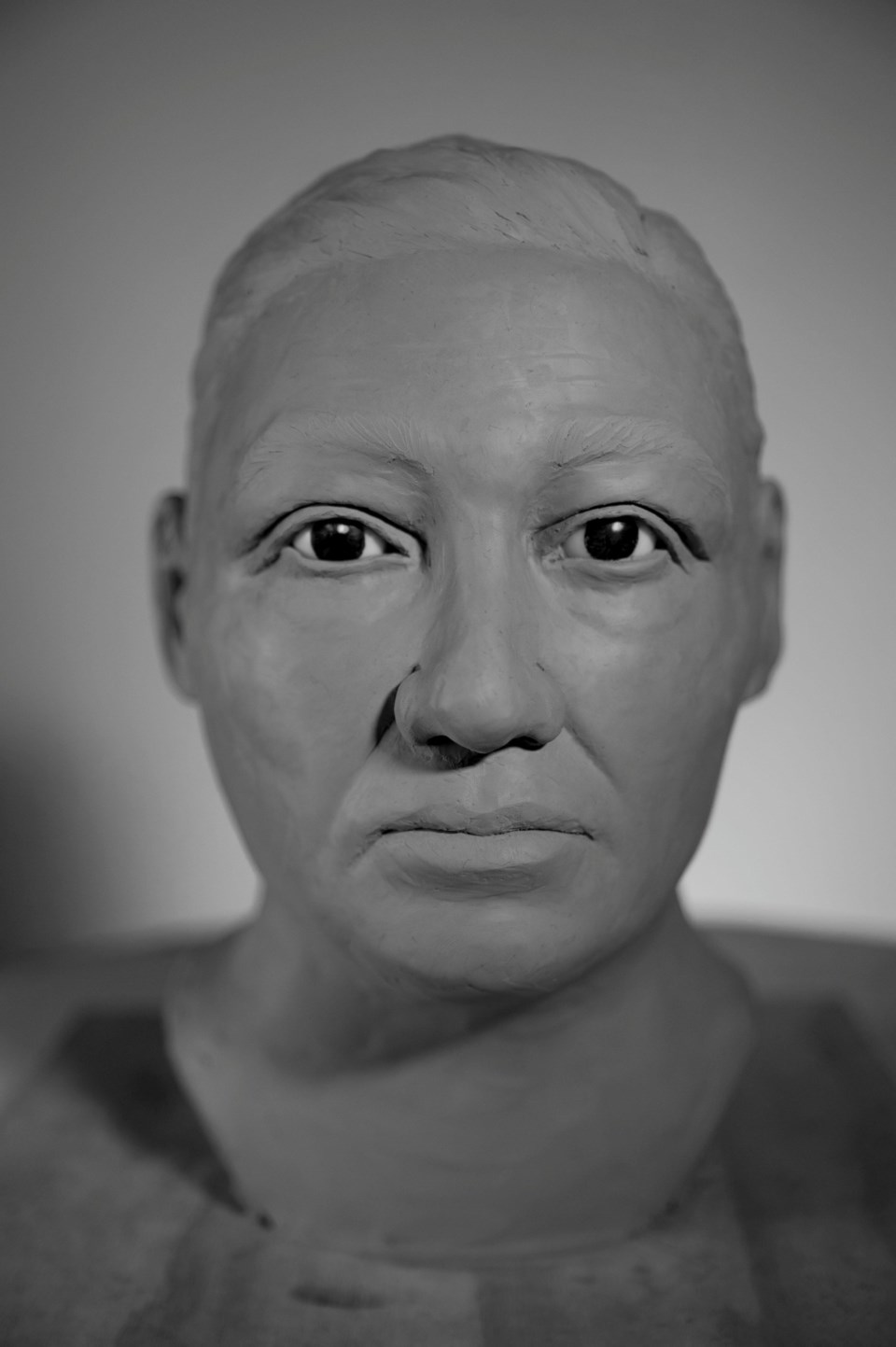

The second Tri-Cities skull reconstruction belongs to a man found in the summer of 1998 in the Coquitlam neighbourhood of Oxford Heights, directly north of the Port Coquitlam cemetery. The man is estimated to measure between five feet four inches tall and six feet, and was found wearing a red cotton shirt and blue jeans.

The other cold cases involved in the project came from across the Lower Mainland, Fraser Valley and Vancouver Island, and into the B.C. Interior. A single cold case found last September at Sandy Cove Beach, N.S. was also included.

The project, described as a unique combination of art and science, began with the BC Coroners Service passing 14 of the 15 unidentified human remains to the RCMP. The skulls were recreated with a 3D printer and, from there, students from the New York Academy of the Arts reconstructed the individuals’ facial features.

“Our hope is that these reconstructions will trigger a memory that results in someone connecting with us or the RCMP, which will lead us to identifying these individuals,” said Eric Petit, director, Special Investigations Unit, BC Coroners Service.

The project builds on earlier collaborations between the BC Coroners Service and the RCMP, including the unidentified human remains viewer, an interactive map released last March that provides information regarding the 179 unidentified human remains investigations still open across the province.

Nationally, the number of unidentified human remains stands at more than 700, according to the RCMP’s national database of missing persons and unidentified human remains. These are the dead-end cases, ones in which there is scant evidence, where DNA and dental records have come up empty, and where no one has come forward to identify the dead.

“This is partnership is a unique opportunity to try to draw new breath into otherwise stalled investigations,” Petit said. “Our hope is that these reconstructions will trigger a memory that results in someone connecting with us or the RCMP, which will lead us to identifying these individuals.”

The New York school reconstructed the 15 faces through its forensic sculpture workshop under the guidance of a senior forensic artist with the U.S. National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children. Since 2015, when it began, the facial reconstruction program has led to a positive identification in four cold cases.

“Every face tells a story and these are 15 individuals who deserve to have their stories told,” said Marie-Claude Arsenault, RCMP chief superintendent and the officer in charge of the Mounties' sensitive and specialized investigative services. “Any detail, no matter how small it may seem, could be the missing piece of the puzzle.”