Metro Vancouver voters have resoundingly defeated a proposal to add a 0.5 per cent sales tax in the region to fund transit and transportation expansion.

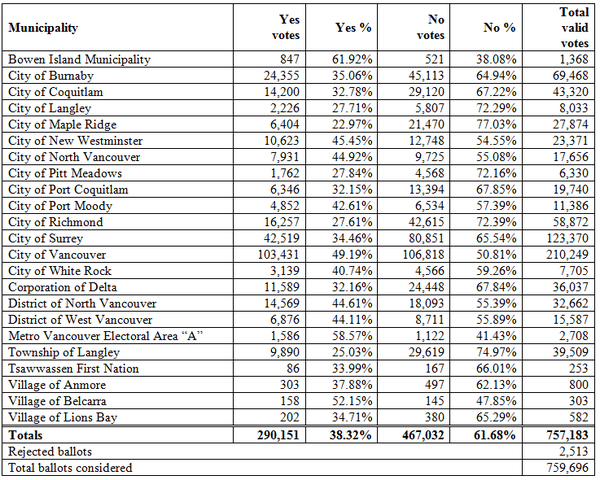

The proposed Metro Vancouver Congestion Improvement Tax that would have funded $7.5 billion in upgrades over 10 years was rejected with 61.7 per cent of voters saying No and 38.3 per cent saying Yes.

The defeat leaves the region without an estimated $250 million in new revenue the tax would have brought to expand transit.

Surrey and Vancouver are expected to try to cobble together their own plan B strategies to built light rail in Surrey and a SkyTrain extension west along Broadway.

But the region will be without the funding required for a broad 25 per cent expansion of bus service, including many more frequent express bus routes that had been in the mayors' plan, nor will it have money for increased SkyTrain, HandyDart, night bus or SeaBus service that was to have swiftly kicked in after a Yes vote.

Surrey Mayor Linda Hepner had warned that light rail would cost local residents more if the sales tax was defeated.

Nor is it clear if light rail in Surrey – assuming it can be built with hefty senior government contributions – will be as viable and efficient in covering its operating costs if it is not accompanied by much-bolstered connecting bus routes to bring riders.

"It sets up a really nasty situation where some people are getting improved rapid transit service in some areas but other people's transit service is being cut back," said Eric Doherty, a HandyDart advocate.

Yes forces had argued defeat would mean worsening congestion as the population grows and demand pressures worsen on a frozen transit system, spurring more transit users to drive instead.

No campaign head Jordan Bateman exploited many voters' unwillingness to pay more – especially to TransLink – and argued more money could be found if cities restrained their own spending and tax growth.

He successfully framed the campaign as a vote on TransLink, which he accused of mismanagement and which had come off major SkyTrain breakdowns and a failure to fully launch its new Compass card payment system on time.

Mayors never wanted the referendum and repeatedly said something as crucial to the region as transit expansion should not go to a public vote.

They had previously wrung a pledge from former Premier Gordon Campbell to allow a new transit revenue source.

But Premier Christy Clark backtracked from his stance and promised in the 2013 provincial election a new tax source for TransLink would only be allowed if it was approved by local voters.

Left with only that path to new funding, mayors agreed last year to the vote and chose a hike in the provincial sales tax from 7.0 to 7.5 per cent within Metro, rather than other options, such as a vehicle levy.

With the sales tax rejected, mayors could still raise TransLink property taxes, which are an existing source, but they are loathe to do so. That option has been repeatedly suggested by the premier.

If mayors hold firm to the need for a new source, it's unclear how that can happen without a new referendum the premier has said can't be held before the next municipal elections in 2018.

In the meantime, observers predict some cities will consider freezing much new development in areas that planners had assumed would be served by better transit in the future. Any clampdown on new home construction could drive real estate prices higher.

One project TransLink is still expected to pursue is the $1-billion replacement of the Pattullo Bridge, to be funded through tolls.

Mayors also intend to pursue some system of road pricing and Transportation Minister Todd Stone has signalled some form of tolling reform will be required if the Pattullo and future Massey Tunnel replacement are both tolled, leaving only one remaining free crossing of the Fraser River.

Several observers expect a major shakeup coming to TransLink.

SFU City Program director Gordon Price said the TransLink board of directors should submit to a reconfirmation of their seats by the mayors' council.

He said the result means the region will likely have to live with "a second rate transportation system" because it's all we can afford.

"Politically, it may be better for the province not to have to commit itself to large scale, sustainable ongoing funding, but to be able to pick and choose those projects it believes are best for the region, but also politically advantageous and affordable," Price said.

More to come