Sydney Willmott spends her days reading between the lines of Metro Vancouver’s trash. As a banned materials inspector at the Coquitlam Transfer Station, she keeps an eye out for paint cans, electronics and clouds of gypsum dust that often pour out of garbage trucks dumping the woody debris of a recent renovation.

To Willmott, the plastic straws, shopping bags and cigarette butts that continue to galvanize municipalities across the province make up a fraction of the mounds of garbage that surround her.

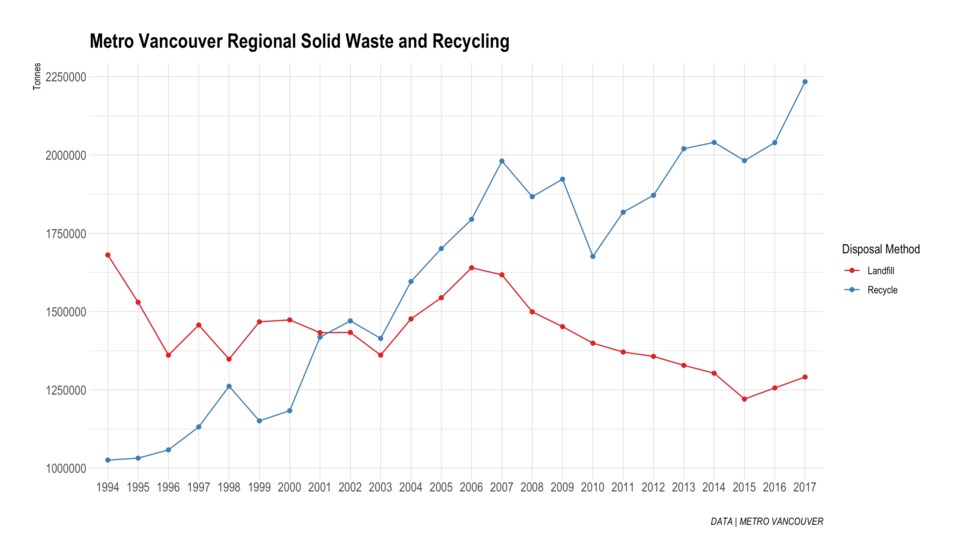

Just as UBC researchers have found more than half the waste on southwestern B.C. beaches is made up of cigarette buts; just as Victoria struggles to ban plastic bags; and just as Coquitlam entrepreneurs look to hit it big with an eco-friendly pasta straw, Metro Vancouver has its eye on shaving down the more than one million tonnes of garbage sent to landfills every year.

Turtles choking on straws and birds suffocating under a plastic bag veil represent a real problem but when you take a look at what makes it into a landfill, these small-volume plastics are not the place solid waste planners are looking to make the biggest gains in recycling, according to Chris Allan, Metro’s director of solid waste operations.

Bulky organics are the largest single category of waste in Metro Van — almost 450,000 tonnes of organics get diverted from landfills every year in the Lower Mainland, according to a July 3 report to Metro’s zero waste committee.

The bulky organic waste that makes it to landfills can quickly become a global problem. Across Canada, 4% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions come from organic waste venting off methane as it decomposes in landfills.

“Most [Metro Vancouverites] are doing quite well but when you consider that more than a third of food produced in Canada never gets eaten, there’s room to reduce organic waste as much as there is to recycle it,” said Allan.

After metro municipalities implemented organics programs between 2013 and ’17, organics recycling jumped by 60%. Much of that success was due to uptake in single-family homes.

Now, Metro’s planners are looking to expand organics recycling in multi-family housing complexes, restaurants and institutions like hospitals.

But ramping up the recycling rate of organics extends beyond compost, raked leaves and grass clippings. Wood waste has become a high-volume problem across Metro’s six transfer stations.

When The Tri-City News recently visited the Coquitlam Transfer Station, a small parking lot of broken wood pallets was hived off from busted appliances and shipping-container-size bins of cardboard. But that’s just a fraction of the wood waste that makes it through the facility.

With the new Coquitlam Transfer Station set to begin operations next year, that’s all set to change. Metro solid waste planners are looking to use the facility as a test lab to pilot a recycling program that would manage the woody side of organics.

The facility will take in somewhere between 60,000 and 100,000 tonnes of wood waste every year, redirecting the combustible scraps to cement kilns, where it will be used as an alternative fuel material.

“The ultimate goal is zero waste but, until we get there, we just have to keep chipping away at it,” said Allan.

WHERE DOES IT GO?

Metro Vancouver throws its trash and recyclables into an open system of transfer stations. Most of the region’s garbage ends up at the waste-to-energy facility in Burnaby where, every year, about 250,000 tonnes of waste is incinerated, and the Vancouver Landfill in Delta, where about 750,000 tonnes of waste is buried.

Anything over that — between 40,000 and 60,000 tonnes over the last three years — gets trucked to railheads in Sumas and Seattle. From there, loads of garbage are packed onto trains that make their way down to a hot, arid stretch of the Columbia River. There, it is buried either in the Roosevelt Regional Landfill in Washington or the Columbia Ridge landfill on the Oregon side of the river.

The question of where Metro Vancouver’s garbage will end up is largely settled until at least 2037, when the Vancouver landfill is expected to reach maximum capacity.

But the search for a new place to put about three quarters of the Lower Mainland's trash is going to need to come sooner than that, says Metro’s director of solid waste operations, Chris Allan. Finding a big enough site that Metro municipalities can agree on could be a challenge, especially with soaring land values.

“I doubt the next landfill is going to be in the Metro area,” said Allan. “It’s just too expensive here.”