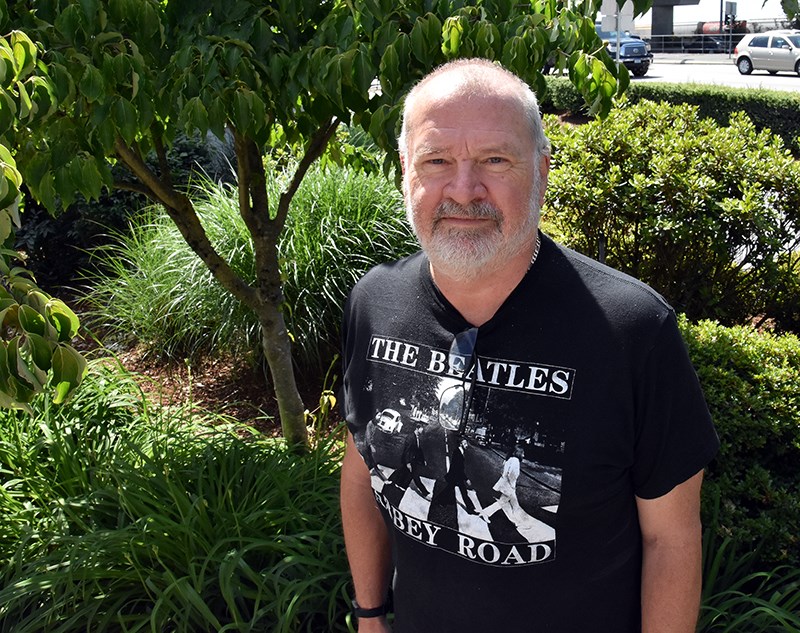

As an advocate for the homeless and addicted, Rob Thiessen has seen his share of tragedy.

But the fentanyl crisis that has gripped the region and killed thousands over the last few years has taken a particularly hard toll, affecting not just the community Thiessen serves but his own mental health.

“I’m burned out,” he said over coffee and donuts at a Port Coquitlam Tim Hortons. “All the death, all the people that I know that have died, it has been kicked up a notch because of the fentanyl crisis. It wears you down.”

Last week, Thiessen retired as the managing director of the Tri-Cities Hope for Freedom Society, a homeless outreach organization he has led for close to two decades.

He made the decision to leave after he started noticing changes in his outlook, he said, adding friends and people he relies on for support suggested it may be time to take a break.

“[They] said, ‘If you push through it… you are going to go toxic,’” he said. “And what that means to me — and I started seeing signs of it — is some of the things that used to bother me weren’t bothering me anymore.”

Being bothered — particularly with seeing homeless and addicted people struggling — is just one motivating factor behind Thiessen’s work.

He was raised in Burnaby as a Mennonite by parents who, despite being lower income, constantly reminded their children how wealthy and fortunate they were compared to most people.

His faith led him to look for ways to give back to the community when he retired from the construction and development industry in 2000 at age 47. A friend from his church in Coquitlam introduced him to the Hope for Freedom Society and, with his business background, it was not long before Thiessen moved into an organizing role.

He said he was drawn to the society because it utilized a curriculum recognized in the secular world balanced with a spiritual component.

“It can be a very positive influence in a person’s life to know there is something bigger than themselves,” he said. “That can help them through what they are dealing with.”

FEARS & FOCUS

In the early days, Hope for Freedom was focused on recovery, operating approximately 75 beds for men and women in houses around the Tri-Cities.

But in 2006, the provincial government asked the society to conduct a pilot homeless outreach program, one of the first of its kind in B.C. The six-month pilot was successful getting people off the streets and eventually became part of Hope for Freedom’s regular work. Today, the initiative serves as a model for more than 40 similar outreach programs across the province, Thiessen said.

Around the same time the pilot program was being conducted, the concept of a cold/wet weather mat program, which turns church basements into temporary shelters on a rotating basis during the coldest months of the year, was first floated by the Tri-Cities Homelessness Task Force. When Thiessen heard the idea, he said he signed on in “two seconds.”

“It wasn’t my vision but I grabbed on to it when I heard it because I knew we could pull it off,” he said.

The first step was getting the churches on board.

For this, Thiessen leaned on his religious background, reminding the more reluctant faith groups of the role their organizations have played throughout history in helping the less fortunate.

“I can speak church,” he said. “I could drop the line ‘What would Jesus do?’ and they would have to say, ‘Absolutely, Jesus would house the homeless.’”

Residents in the community were less enthusiastic.

People packed a public hearing in Coquitlam to speak against the initiative, setting a record for the longest council meeting in recent memory. As the spokesperson for Hope for Freedom, Thiessen was often the target of vitriol from residents who accused him of endangering their children and bringing crime into their neighbourhood.

“There was a lot of shrill stuff going on,” he said. “I try to stay calm. It is very difficult to hurt my feelings and it is very difficult to rattle me.”

Following the contentious debate, the rotating shelters were approved and stayed in service without incident until a permanent homeless shelter was built in 2015 at 3030 Gordon Ave. in Coquitlam.

Last fall, an increase in demand for shelter space prompted BC Housing to approach Hope for Freedom about re-launching the mat program for winter 2018/’19. When several churches had to have temporary use permits approved by Coquitlam council, neighbours again spoke against the proposal, though not in the numbers seen when the plan was introduced in 2007.

“Those fears will never go away, I don’t think,” Thiessen said. “But we have softened the blow.”

A lot of people do not understand how someone becomes homeless or addicted and often believe the situation is the result of an individual's bad decisions, he added.

But of all the people that have made their way through Hope for Freedom’s recovery programs, Thiessen said he has yet to meet someone who is there because they partied too much in high school or college.

“Most are medicating a hurt,” he said. “We try and drill down to where that hurt originates.”

A WAY OUT

Thiessen’s full-throated support for programs that emphasize recovery and drug and alcohol abstinence has put him at odds with other low- or no-barrier shelter operators in the region.

While he agrees the harm-reduction model can work in certain circumstances — Hope for Freedom has even “dipped its toe in” with a methadone taper program — he said some organizations are too quick to label a person an addict in need of management rather than sobriety.

“I firmly believe we have to continue to offer people a way out,” he said.

For evidence that recovery can work, Thiessen only needs to look around the room during a Hope for Freedom staff meeting.

“Most of my former staff came through our program as broken-down drug addicts,” he said. “And they got their lives back. They got their families back.

"We have helped thousands of people. You don’t need to use drugs in order to have a successful life.”

And as the death toll from the fentanyl crisis continues to rise, Thiessen said getting people off of drugs is more important now than ever.

“I have never gotten used to it,” he said, of the number of deaths he has seen over the last few years. “I don’t ever want to get used to it. I want it to impact me. Everyone of those people that died has a measurable value. They are valuable. They were born for a purpose and that was not to become addicted and die.”

'WE NEED TO HELP'

While the strain of the fentanyl crisis may have hastened his retirement, Thiessen said he feels a strong sense of accomplishment as he leaves his role. There is a lot of work still to do in the Tri-Cities but he points to the hundreds of people Hope for Freedom has helped shake addiction or get into stable housing.

“These have been the best years of my life,” Thiessen said.

And he believes he is leaving the society in capable hands.

Dennis Fagan, a longtime administrator, will take over as the executive director while Andrea Corrigan, an outreach worker, will move into an assistant role. Both have been with the organization for many years and understand its unique role in the community, Thiessen said.

“Hope for Freedom is open for business,” he added. “They will find new ventures. We have always been a little edgy. We have pushed the envelope and I believe that will continue to happen.”

Getting a handle on the homelessness and addiction issues in the Tri-Cities will take a contribution from everyone, he said. That could mean volunteering or donating money. It could also mean accepting some of the discomforts a person may feel about a shelter or treatment facility opening up in their neighbourhood, he added.

“We need to sacrifice a bit,” Thiessen said. “If there is an impact that you don’t like, suck it up, because we need to help these people.”