Many Tri-City residents woke up to another orange orb in the sky Wednesday morning as smoke from wildfires in Washington, Oregon and Northern California continued to blanket the region in fine particulate matter.

On Sept. 16, the region entered its ninth day under a special air quality statement, a stretch that at times gave Metro Vancouver the unenviable crown of most polluted air of any city in the world. As firefighters south of the border work at suppressing the fires, Environment Canada predicts smokey conditions will remain until the end of the week.

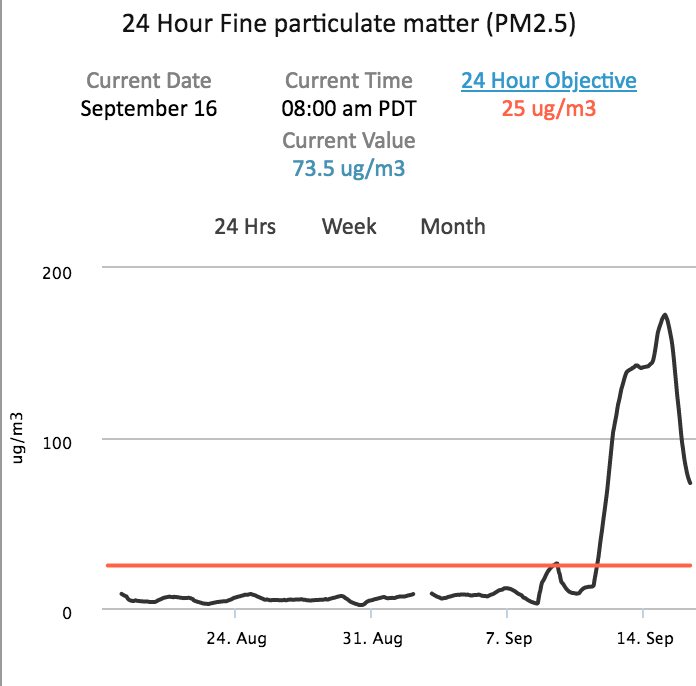

At a Port Moody air quality station, concentrations of fine particulate matter dipped under 60 micrograms per square metre this morning, down from a high of over 234 on Monday but still well above Metro Vancouver's safety threshold of 25 micograms per square metre.

But choking air isn’t the only side of fire in the Lower Mainland’s future.

“What’s happening in the United States in the west right now is going to happen again in B.C., in Alberta, in the Yukon and in NWT. It’s all part of that rhythm we’re in and the rhythm of experiencing intense fire events seems to be increasing,” said Meg Krawchuk, a former SFU researcher now in Corvallis, Ore., who studies the geography of wildfire to understand its ‘recipes’ from one place to the next.

Up and down the West Coast, Krawchuck sees the same factors combining to create tinderbox conditions: one year, nearly synchronized across three U.S. states due to soaring temperatures and an extreme easterly wind event, another year in B.C. after drought-like conditions, years of poor forest management and generations of creeping urbanism set the stage for disaster.

“It’s reckless to ignore that climate change component,” said Krawchuk. “That underlying drumbeat, which is a directional change in climate towards aridity and dryness is something that touches all of these fires.”

She added: “It’s going into that pace of not ‘what if’ but ‘when’ that next round will come to your back door… We’ve been messing with the natural tempos with fire suppression. But we know that fire will express itself across these landscapes. We can’t make it go away. So how do we learn to live with it?”

Tri-City residents are often reminded of the wild nature of their suburban communities, how being part of a population and infrastructure butting up against the urban-wild interface comes with consequences and responsibilities. But it’s not just black bears and cougars on Burke Mountain that we need to think about, warns Krawchuk.

A lot of people in Oregon were caught by surprise by last week’s big wind events, even as red flag warnings were blasted across communication channels.

“But you can only hear the news if you listen for it. Being aware of what’s happening is critically important,” said Krawchuk.

And now, as the tragedy grips so many communities across the American West and beyond hearing those stories from a distance can be as important a step in preparing for our own future of fire as an evacuation kit and a HEPA filter.

“When you’re not in it, it’s smoke,” she warns. “Listen to the heartbreaking stories and actually digest what’s being lost to try and remind yourself of why it matters.”