The city of Coquitlam released a new draft cemetery services plan this week that sketches out a roadmap for the future of Robinson Memorial Park Cemetery over the next 30 to 40 years.

The plan comes after the city realized, if nothing were done, traditional burial plots would run out in the next three to four years.

But opening up space for more burials has necessitated a re-imagination of a traditional cemetery.

In a metro area where land is a premium and municipalities struggle to find solutions to a housing crisis, they also now find themselves grappling with the rising cost of dying.

As Coun. Bonita Zarrillo put to council last June, “If no city decided to expand or zone, how does B.C. as a province and Canada as a country plan to deal with death as a society?"

Based on population growth and data on burial preferences, the city of Coquitlam calculated they would need to bury or cremate 31,000 people over the next 50 years.

At the moment, the cemetery recovers its expenses through a direct cost-recovery, meaning it breaks even with every burial.

The new draft plan proposes price hikes that range between 10 and 20 per cent to keep up with rising costs of traditional burials and cremations.

To ensure there’s enough cash on hand to maintain, operate and grow the cemetery, the draft plan proposes to help establish a cemetery capital reserve fund, which at $17.1 million by 2047 would cover the costs of buying and developing new land at an unspecified point in the future.

Across the province, municipalities are often the ones running public cemeteries. That means both a certain level of democratic accountability and access.

In the same way Coquitlam residents get priority when it comes to public services like the library or community pool, those looking to be buried at Robinson Memorial get certain advantages if they live (or lived) within city limits.

In the case of cremation, non-residents will have to pay 50 per cent more than a resident and 25 per cent more than a former resident, according to the new draft plan.

In other ways, costs will increase across the board. For example, marker permit fees will nearly double, from $92 to $176.

It’s not just the cost of dying that will change with the new plan. Last summer, the city of Coquitlam conducted a survey of nearly 600 residents, asking them a range of questions about their plans for death and how those would fit in with the future of Robinson Memorial Park Cemetery.

About a third of respondents said they would prefer to be cremated and buried in the ground; 44 per cent said they would like to be cremated and memorialized in a niche wall; and 33 per cent said they would prefer a green burial in which their ashes are layed to rest in a reforested area with a common marker.

That’s a major departure from traditional burials, which not only are more costly but also take up more space, said Lanny Englund, the manager of parks planning and forestry who oversaw the draft plan.

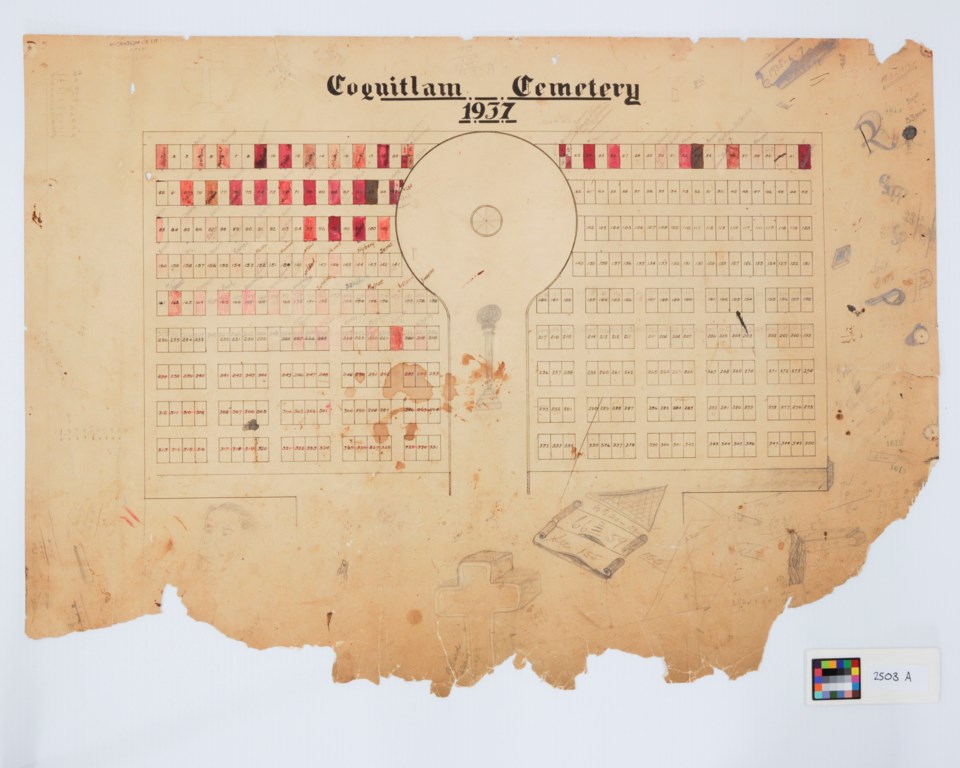

When plans were drawn up for Robinson Memorial Park Cemetery in 1937, many would likely have gasped at the thought of walking over graves. But as the Tri-Cities grow, the grid of paths that once led to and divided the interred will likely vanish.

“As land becomes more valuable we’ll use these pallbearer walkways for cremated and full-burial remains,” said Englund.

Traditional expectations around what is and what is not acceptable appear to have changed significantly since the cemetery was first built. According to last summer’s survey, 94 per cent of respondents supported the idea of allowing new family interments in an occupied plot after about 40 years.

“We’ve come to a very good spot,” said Coquitlam Coun. Brent Asmundson. “We’ve got a lot of support from the public.”

The first phase of the draft plan is expected to stretch from the time it’s approved (Asmundson expects it will go to vote at council before the summer) to 2020, and will include clearing over 1,200 green burial plots and 380 traditional plots. At this early stage, the plan also calls for installing columbarium pedestals and memorial boulders.

Phase two and three, expected to role out in 2023 and 2030, respectively, are proposed to include the construction of new columbarium walls and infill even more space that would otherwise be left open in a traditional cemetery.

Still, with the cost of land so high, Coun. Asmundson questions whether the plan will go far enough to keep the cemetery in public hands.

“Do you stay in the business of providing services or do you let the private sector step in?” he said.

— With files from Grant Granger