Port Coquitlam Fire Chief Nick Delmonico says he stands by his controversial memo to city staff instructing them ask for "fire" instead of an ambulance when calling 911 in case of a medical emergency.

The direction came through the recently revealed memo, dated March 19, 2019, and marks the latest salvo in a protracted spat between the PoCo Fire and Emergency Services and the BC Ambulance Service.

Unbelievably inappropriate.

— Send Paramedics - Ontario (@Send_Paramedics) April 8, 2019

Port Coquitlam, Fire Chief has asked city staff to ask for "Fire" when calling 911 for medical problems so fire fighters can be redundantly dispatched to calls they would otherwise not be tiered to.

This is an egregious over stepping & undermines 911 pic.twitter.com/xjaCLPEgDL

In an interview this week with The Tri-City News, Delmonico said city staff should ask to speak with fire dispatch when seeking help in a medical emergency.

“We're more in tune with the area, so we're always quicker than the ambulance service,” he said.

In May 2018, BC Emergency Health Services (BCEHS) changed how it triages emergency calls — known as its clinical response model — dispatching ambulances and paramedics in a way that it says prioritizes the most life-threatening calls.

But while advising people to take a cab and relying on a nurse line has freed up a lot of paramedics once overwhelmed with less serious calls, both Port Coquitlam’s fire chief and mayor say significant wait times plague the system.

“We have been raising our concerns about the consequences of those response times for several years now,” said Port Coquitlam Mayor Brad West. “I am not satisfied that they have made any adjustments to address that issue. It's extremely frustrating.”

On the most serious calls — cardiac arrests, asphyxiation and car accidents, for example — the fire department attends nearly every incident. It’s the middle range — the orange calls under the new system — where Delmonico has faulted the ambulance service for slow response times.

Under the new model, BCEHS does not notify firefighters when it receives a moderately urgent call if an ambulance is expected to arrive on scene within 10 minutes, BCEHS spokesperson Shannon Miller said in an email to The Tri-City News.

Problems in that range include convulsions, seizures, haemorrhages, chest pains or a fall, and they can be coded high or low, said Delmonico. That leaves it open to the judgement of a dispatcher, which can be far from foolproof when a caller is overwhelmed with an emergency, he said.

Delmonico has been speaking out on ambulance wait times for several months and told The Tri-City News in January: "They seem to think the system is infallible."

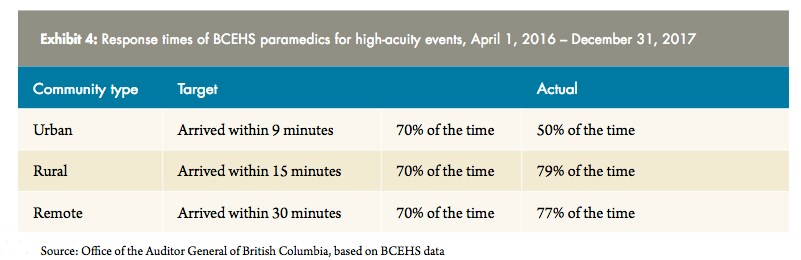

In February, B.C.’s auditor general, Carol Bellringer, echoed some of the chief’s concerns in a report that criticized the ambulance service for taking too long to reach patients with severe injuries and illness.

Province-wide, ambulance response times in urban areas achieved the nine-minute or less target 50% of the time in 2016, well below BCEHS’s 70% target. In 2018, crews hit that target response time 51% of the time, improving a single percentage point after more staff was added and new procedures put in place. In some cases, paramedics didn’t arrive for 45 minutes.

At the time, Bellringer said BCEHS is doing a number of things to reduce response times, including increasing the number of paramedics and ambulances, as well as introducing the new dispatch system under question.

In Port Coquitlam, BCEHS data shows a relatively steady call volume over the last few years, increasing to 4,732 in 2018 from 4,514 in 2016, a less than 5% jump.

In every triage category, Miller wrote, the median response time has dropped since the new system was implemented, including the controversial orange category, which fell to 12:42 in 2018 from 13:16 in 2017.

Neil Lilley, executive director of the BCEHS, points to these numbers when he says much of the concern around wait times is unfounded, adding that anyone who has a medical emergency is putting their lives on the line if they delay calling BCEHS operators.

Lilley noted emergency medical call-takers are trained in walking people through how to perform CPR, find and use a defibrillator, deliver babies, control bleeding and clear an obstructed airway.

“Fire dispatch aren't trained in medical advice and they're not qualified to give anybody any kind of medical advice over the phone,” Lilley said.

Directly calling fire dispatch can also tie up firefighters on low-priority calls, making them unavailable to respond to the most critical medical emergencies, according to Lilley. “And that's what we need them there for,” he said.

But the BCEHS numbers don’t line up with the response times tracked by the city of Port Coquitlam, which in the eyes of the mayor and fire chief means residents are aren’t getting the emergency care they deserve.

“Our information shows us that the ambulance response times in Port Coquitlam are some of the worst in Metro Vancouver. It's not an acceptable situation,” West said, adding a blunt conciliatory gesture.

“I'm not interested in turf wars or pissing matches between groups of first responders. I respect all of them. But the reality is, we need to get care in a very timely manner to Port Coquitlam residents who need it.”

Just as the controversial memo appeared to widen the gap between the two emergency services, the two sides showed signs of coming together.

In the hours leading up to the April 9 Port Coquitlam council meeting, Lilley and BCEHS CEO Barb Fitzsimmons spoke over the phone with Delmonico and PoCo's chief administrative officer, Kristin Dixon. Both sides agreed to sit down to try to work out the best course forward.

“This is the first time they've offered to come over and sit with us,” said Delmonico. “That's a very positive development.”

Stefan Labbé