Is it important to know how your child is progressing in school? Of course it is, or should be. To gain a superficial idea, there is the occasional report card as required by the Ministry of Education. Boards of education must provide parents of students with a minimum of five reports describing students’ school progress.

That’s a start.

A meeting with the teacher when your questions are prepared based on the research you’ve done about the expectations for that grade — that’s a good frame for a teacher-parent meeting and learning about an individual child’s progress.

Better than numbers or letters on a report card, anyway.

How about your child’s progress in comparison to others in his/her class or cross-school grade? That’s of some significance, but it introduces factors not necessarily under your or the teacher’s or your child’s control. Every child is different, we know that, so comparing their report cards reveals very little.

Children learn differently and don’t learn in lockstep with each other. I’ve heard it said that it’s more like a dance; a step forward, a step sideways, even a step back sometimes.

At least that’s how it has always been with me as I try to learn something new.

Is it important to know how your child’s school shapes up compared with other schools in the district? Well yes, as long as you take into account that there is a mountain of unassailable research that says that the demography of a school’s population can be a factor in comparing one school with another.

How about comparing academic results from your school district or your province compared to, say, Finland or Singapore?

That’s a very different and multi-layered question. More than anything, it’s a political question.

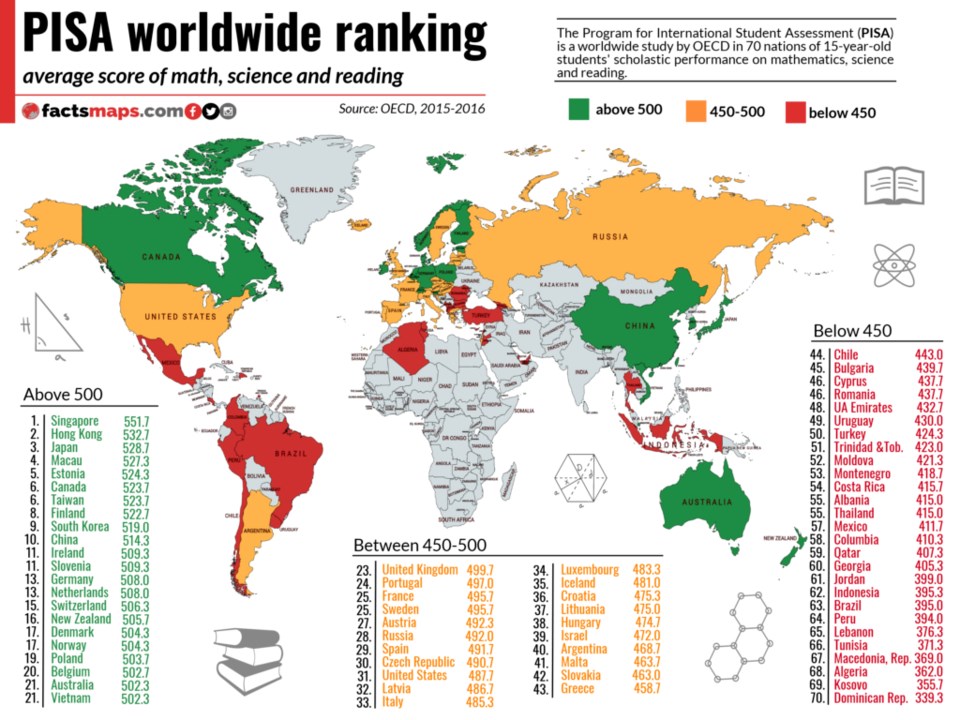

For what it’s worth, on the 2018 international Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Canadian 15-year-olds placed sixth in reading skills behind China (including Hong Kong and Macao) and Estonia.

In math skills, Canada’s 15-year-olds ranked 11th behind those same countries, plus Japan, Korea, the Netherlands and Poland.

A politician might, predictably, jump on that and make an impassioned speech about the poor state of education (and everything else) in Canada.

A more useful response would be to consider that those 2018 statistics are comparing education systems absent any considerations of relevance, cultural beliefs and “actionability” in their national context. “Actionability” means data is actually being used at a provincial or national level for policy making, monitoring or strategy development.

So PISA results are interesting and valid enough to provide fodder for a dozen or more PhD theses examining the cultural factors influencing the differences and the expectations of other national systems. But what do they mean in terms of your child’s progress?

Some of the assesment experts who are directly involved with PISA point out that PISA should be considered as simply a single source of information.

Relying solely on PISA to judge how well B.C.’s students are reading, for example, would be a mistake when there is also an assortment of parallel reading assessments periodically administered by the province that also should be considered when judging how well the system is performing.

These include B.C.’s Foundation Skills Assessment, designed by experienced B.C. teachers, the Pan-Canadian Assessment Program, designed by Canadian experts, as well as the Progress in International Reading Literacy, developed by international reading experts.

Aside from all that, beyond all that high-profile statistical assessment, most parents are mainly concerned about two central areas relating to their child’s education:

• Is my child happy at school?

• Is my child making good progress at school?

The first of these questions is vital, and for most parents, it is easy to tell if their child is happy at school through discussion with their child and the class teacher. It seems a statement of the obvious, but a happy child will do well at school.

The second question is not as easy for parents to answer.

An individual child’s progress is about moving forward in learning and developing new skills. It is not about comparing one child with another; it’s about looking at how far a child has moved on in their learning in relation to their own starting point.

Finally, and I’m aware that during a 13-year public school career your child could meet as many as 30 teachers, an important question for a parent to consider is “does my child like the teacher?” Parallel to that, but possibly evident in the parent-teacher interviews, is “does this teacher like my child?”

The importance of those questions is probably more significant at the elementary-school level, but nonetheless might clarify aspects of the teaching/learning experience your child faces every day.

The school has your child for 5 1/2 hours per day for 185 days. You have your child for the other 18 1/2 hours, and 365 days every year.

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.